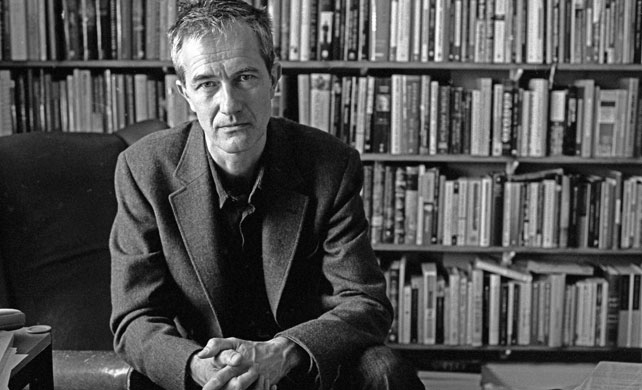

Dyer, Geoff. Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room, Pantheon, New York, 2012 (232pp. $24)

For 20 years or so English writer Geoff Dyer has landed his reader smack in the middle of an archly idiosyncratic search for post-postmodern literary meaning. He has written serious books about photography and jazz books about yoga having nothing to do with yoga, and a long jesting foray about researching a biography of D.H. Lawrence, ending in success disguised as failure.

In a way, Geoff Dyer has tricked up Tristram Shandy, cross-bred it with Lady Gaga, and come up with an insightful, audacious, deeply personal, often hilarious and entertaining approach to literature. He is one of the most interesting writers at work today in English—even his failures inspire.

His new book, “Zona”, will challenge readers to stick with Dyer as he submarines his way through many underwater frontiers including Dyer’s personal feelings and aesthetic judgments about many classic and not-so-classic movies, musings on the relations between LSD trips and cinematic voyaging, old girlfriends, missed sexual opportunities in youth, and even the place of quicksand (yes actual jungle quicksand) in imagination. Even panic-stricken, beside the point, or off-base, Dyer manages to connect the dots.

Ostensibly, “Zona” is a book about the great Soviet director Andrei Tarkovsky’s “Salker” (1979), a dystopian masterpiece considered by some to be one of the most boring films of all times (and by others a mysterious work of genius).

Dyer muses: “What kind of writer am I, reduced to writing a summary of a film? Especially when there are few things I hate more than when someone, in an attempt to persuade me to see a film, starts summarizing it, explaining the plot, thereby destroying any chance of my ever seeing it?” Then, of course, Dyer proceeds to explicate the 2 1/2 hour film scene by scene.

The action of “Stalker” involves the mock odyssey of three Russians, the Writer, the Professor, and the leader Stalker, who wander through a polluted, apocalyptic area called the Zone in search of the Room, where one’s secret hopes and desires reach fulfillment. The movie creeps along, though, wondrously, Dyer’s book gallops.

Dyer, a movie fanatic of long standing, explains Tarkovsky’s many troubles filming the movie, his disputes with a jealous wife, the heart attack that sidelined him for months, lost footage and destroyed film stock, an earthquake in Tajikistan that disrupted filming and caused the crew to exchange the Central Asian desert for a polluted river region in Estonia where, it is thought, Tarkovsky and others were exposed to cancer-causing chemicals. Tarkovsky died of cancer.

“Zona” becomes Dyer’s Room, the place where he remembers himself remembering the movie, simultaneously a hall of mirrors and kaleidoscope, echo-chamber and reverb-amp. “The first few times I saw “Stalker” were during a phase of my life when I took LSD and magic mushrooms regularly,” Dyer recalls.

And in an extended footnote (there are dozens of extended footnotes), Dyer observes that, “The prominent place occupied in my consciousness by “Stalker” is almost certainly bound up with the fact that I saw it at a particular time in my life…I suspect it is rare for anyone to see their—what they consider to be the greatest film after the age of thirty.” How true.

How wonderful, Dyer is saying, to be young and in love with a movie that nobody cares about or wishes to see or, mostly, even remembers.

How wonderful it is to take one last longing look before we’re all turned to pillars of salt by the everyday grind.