Bagley, Will. With Golden Visions Bright Before Them: Trails to the Mining West, 1849-1852, Volume 2, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2013 (480pp. $45)

Bagley, Will. With Golden Visions Bright Before Them: Trails to the Mining West, 1849-1852, Volume 2, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2013 (480pp. $45)

That there was placer gold in California’s Sierra Nevada was secret to many. Californios had found it in San Feliciano Canyon during 1842. Even the sight of a glittering nugget of the stuff in the trail race of a sawmill James Marshall was building in January 1848, was nothing new either, and nothing much happened about it until a wily trader named Samuel Brannan charged up Montgomery Street in San Francisco on May 10 that year, waving a bottle of gold dust above his head and shouting, “Gold! Gold from the American River!”

Then, when Colonel Richard Mason, military governor of California under American dominion sent a tea caddy containing 230 ounces of gold (more than 14 pounds!) to the War Department in Washington, rumors were confirmed that gold in California would pay for the Mexican War more than a hundred times over. Feisty, imperial President James K. Polk exulted in the news. “The Mississippi,” he said “so lately the frontier of our country, is now only the center.” American went gold crazy, and the rush was on.

Brilliantly told with an abundance of extraordinary detail, “With Golden Visions Bright Before Them” builds on Will Bagley’s magnificent first volume of the Overland West Series, to bring readers an unparalleled heroic epic more complex, challenging and contentious than simple legend has ever had it.

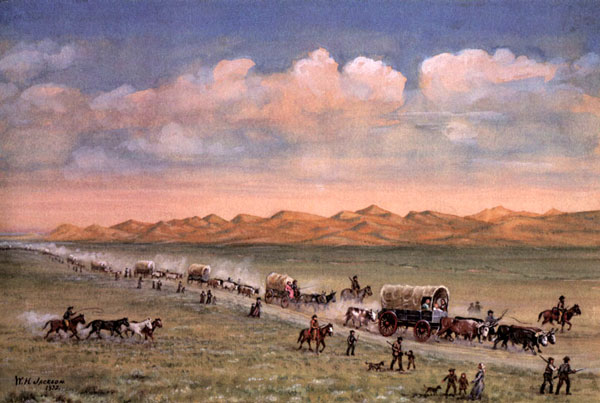

Bagley’s access to primary source materials is itself heroic. The author consulted kore than 500 new personal letters, journals, government documents, newspaper reports and folk accounts, and apparently examined a horde of paintings, drawings and renderings, many in private collections never seen. To capture a sense of the journey and its terrain, main trails, side trails, cut-offs and dead-ends, Bagley follows the western trek of Forty-niners and Oregon-bound soldiers and settlers in a mile-by-mile account of exhilaration, suffering, sacrifice and often death.

The Gold Rush began a new era in overland trail history, which saw nearly a quarter million people undertake the journey, most of them during 1849-52, going to California via the Humboldt River, then up and over the Sierras at Donner or Carson passes. Most of the sojourners were men, many of them footloose vagabonds, younger sons with no hope of inheriting property, avaricious no-goods, brigands, even downright thieves and cutthroats. Others, a significant number, were professional men like lawyers and physicians. Tradesmen of every kind joined the rush for gold, including carpenters, chemists, blacksmiths, wagon-makers and merchants. Most traveled in “companies” of a dozen wagons or more, usually organized in military-style with leaders and scouts, though this organizational structure often broke down on account of intemperance, sour luck or disease. Even then, a cholera epidemic was sweeping up the Mississippi River Valley in 1848.

Three months after he left office, President Polk was dead in Tennessee, and the disease that killed him crept up the valley, killing thousands in the unhealthy river towns. Cholera also swept through the hordes of gold seekers, who carried it to the Plains Indian Tribes. Of the 100,000 or so who crossed to California to find gold, perhaps 5,000 died of disease.

Bagley’s grand work is eloquent. “Going to see the elephant!” became synonymous with going to California (some saw only the tail and some didn’t like the elephant when they saw it). No aspect of trail life escapes Bagley’s sharp eye—clothes, equipment, wagons (wagons were colorfully decorated in pink, red, green and blue paint, most with slogans sloshed on the canvas), family life, music, religion, disease, hardship, trading, Indian encounters, thievery, and a multitude of other topics.

Bagley’s deeply enjoyable history is thus tinged with horrific disaster, wherein the American Dream for the first time comes to include the idea that it is our birthright to get rich quick. As Bagley writes, “The notion that anyone ever learns anything from history is dubious, but that does not prevent the past from lighting the way toa more just, tolerant and sustainable future.”

That’s one elephant Americans haven’t seen yet.