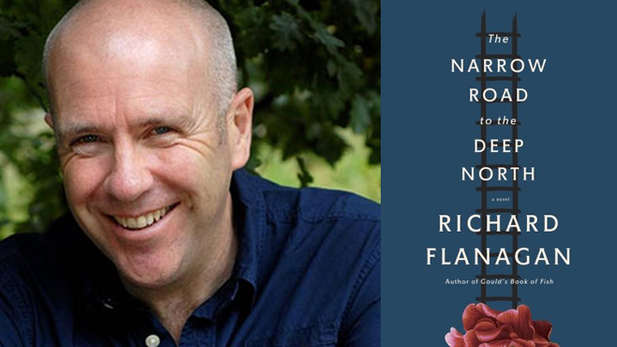

Flanagan, Richard. The Narrow Road to the Deep North. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2014 (334pp. $26.95)

A happy man has no past, while an unhappy man has nothing else. In his old age, Dorrigo Evans never knew if he had read this or had himself made it up.

The great unhappiness at the heart of Richard Flanagan’s new novel, “The Narrow Road to the Deep North”, is the death and pointless pathetic suffering of millions in a war that began with the fall of Singapore and ended in atomic holocaust over Hiroshima. In between, commencing in February 1943, came the Japanese effort to build a railway—“The Line”, connecting China, Burma and India, a line which would allow the Japanese to supply their over-extended forces by land, the logic of which entailed the conquering of India. Such was the mystique of the Japanese martial spirit that it allowed the Japanese Emperor to assume the mantle of God and direct that hundreds of thousands of slaves, including twenty-two thousand Australian POWs, be forced to work laying track.

Today, at the Yasukuni Shrine in Toyko, stands steam locomotive C 5631, proudly displayed in a museum that forms part of Japan’s unofficial national war memorial—a shrine that also shelters the Book of Souls, listing over two million names of Japanese war dead, men whose memories are untarnished now by evil, though among the two million are slightly over one thousand who were convicted of heinous war crimes, among those crimes the mistreatment, torture and murder of Australian POWs working on The Line.

Flanagan, who lives on the island of Tasmania, just off the southern coast of mainland Australia, is perhaps best known in the United States for his novel, “The Death of a River Guide”, though his five other works have received numerous honors and have been published in twenty-six countries. At the center of this ambitious and, at times, turgid work, is a young Australian surgeon named Dorrigo Evans whose life in 1943 centers on the daily struggle to survive in a prisoner of war camp on The Line, where the men under his command, for whom his medical care and officer status become precarious life-lines to the Japanese guards and commanders, are subject to pitiless daily beatings, overwhelming work quotas, and diseases like cholera and malaria. Their suffering has no virtue, no point; it is remorseless and nihilistic, though everyone in the camp prays for relief to an absent deity.

Studded with flashbacks from Dorrigo’s perspective as an old, famous medical man whose survival in the camps has become a national myth, Flanagan’s novel delves into the nature and meaning of war and death, love and intimacy, adultery and even celebrity. Dorrigo’s comrades in the camp are Australian types: Bonox Baker, an enlisted man, who says nothing for years after he returns from Burma and then one night takes a shotgun to his head; or, Jimmy Bigelow, or “poor old Lizard Brancussi”, or Sheephead Morton. And then there are the men who don’t come back; some like Darky Gardiner whose deaths are chronicled by Flanagan with horrific specificity.

Dorriogo’s unhappiness, however, stems not only from his war experiences; but, also, from a chance love affair conducted just before the war in his uncle’s bush home with his uncle’s young wife Amy, while his uncle is away on business. Dorrigo, already engaged to a “superior” woman named Ella from a good family, experiences in one week before he leaves for the war what can only be called passion without conscience. Miraculously, Dorrigo survives the war and returns to marry Ella, thinking mistakenly that Amy has died. She has not died. Thus a second and perhaps greater unhappiness comes into Dorrigo’s life though a side door. This unhappiness is a life lived without love.

“The Narrow Road to the Deep North”—the title refers to Basho’s great travel journal of the same name and connotes Japan’s connections to Zen, meditation, the martial spirit and asceticism, is Flanagan’s conscious effort to write a Big Novel. Crisscrossing the generations and including the stories of Japanese prison guards upon their return home after the war, Korean lackeys convicted as war criminals while the “officers” go free, home front ladies who keep the lights burning back in Queensland, and a smattering of Australian survivors who go home, (“They die off quickly, strangely, in car smashes and suicides and creeping diseases.”) Flanagan’s novel sometimes hits hard and sometimes wanders, wading into the deep water of repetition, as Big Novels sometimes do.

At the end, Dorrigo Evans in old age lies on a cot reading. He stumbles on a line or two: “Love is two bodies with one soul.” He thinks to himself: “He would live in hell, because love is that too.”

It may be that the novel, with its multi-generational narrative, its major themes of war and love (peace?), and it’s focus on the Australian national character, is engaged in the erection of a national literature by building on the experience of Australia’s “greatest generation”. Proceeding as it does in flashes of brilliance followed by pages of tedious repetition; relying as it does on haiku and Victorian poetry; assuming that World War II was Australia’s chance for an Illiad and Odyssey, Flanagan has produced a novel of hits and misses. Some of it is beautiful, as in the prisoner of war passages. Some of it is tawdry, mundane and repetitive, as when Dorrigo lies in bed with his mistress, expostulating on life while rain hammers down and they sweat.

Perhaps every Big Novel is flawed and beautiful both, just as love is both heaven and hell.