Drury, Bob and Clavin, Tom, The Heart of Everything That Is: The Untold Story of Red Cloud, An American Legend, Simon and Schuster, New York, 2013 (414pp.$30)

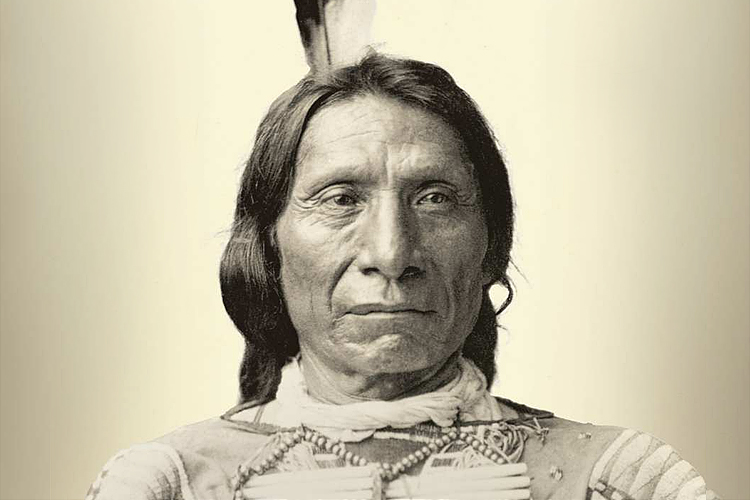

Among the Bad Face Brule band of Sioux living in the western Nebraska panhandle was a brave called Lone Man, whose Oglala wife, Walks as She Thinks, was pregnant with her first child. Preparing to give birth, Walks as She Thinks spread a blanket on the sand beside Blue Water Creek. That night, meteors streaked through the cloudy sky, an astronomical event interpreted by Lone Man as an omen. The Brules agreed with Lone Man’s decision to name his son Makhpiya-huta, which by the Whites was translated as Red Cloud. The year was 1821 and the infant was to become the Sioux nation’s war leader in the Powder River war forty-six years later, and the Plains Indian’s only strategic warrior (though there were many Indian heroes) in decade-long struggle by the united tribes to preserve a tiny fraction of their culture and land.

Just when the general reader might think that everything has been written about the wars of the northern plains, modern historians and researchers continue to produce astounding feats of research, reinterpreting, analyzing, and reorganizing the record to produce works that are not only original, but also detailed. The Heart of Everything That Is is grand in scope and beautifully observed, telling not only the story of Red Cloud’s life and his 1866-68 struggle called, by some, Red Cloud’s War (though the Brule’s were joined by a large coalition of Indian tribes and bands, some of whom were former enemies), but also taking the reader on a tour de force of historical story-telling.

Bob Drury, an independent historian and foreign correspondent who has reported from Iraq, Darfur and Afghanistan, is the author of nine books and is a magazine writer of note. His partner Tom Clavin has written sixteen books and was a writer for The New York Times, and also the investigative features correspondent for Manhattan Magazine. Together, these two freelance writers have managed a feat of scholarship that interweaves ethological brilliance and an insightful reinterpretation of Indian culture from the point of view of the Sioux and their allies, mainly the northern Cheyenne. The book is accompanied by a set of excellent maps and photographs, and an up-to-date bibliography.

Beginning with Red Cloud’s birth in 1821, the authors take the reader on a galvanizing ride through time and space, an ethno-sphere peopled by unforgettable characters like Spotted Tail, Sitting Bull, Young Man Afraid of His Horses and, notably, Crazy Horse on the Indian side, and Jim Bridger, William Fetterman, Colonel Henry Carrington, “Little Phil” Sheridan, and many others on the “civilized side”. Most impressive, perhaps, is the books’ deeply convincing explanation of Indian cultural life, including war-making, the warrior ethic, and tribal political undertakings and procedures. Equally stirring is the authors’ ability to integrate contemporary diaries, journals, eyewitness accounts, and genuinely authoritative firsthand sourcing into an utterly mesmerizing account of how, for a short time, Red Cloud managed to hold the Americans at bay despite being outgunned, outmanned and out-supplied.

The centerpiece of the book is the famous Fetterman Massacre, in which 88 members of the Second Cavalry were killed by a coalition of Indian warriors about eight miles outside Fort Phil Kearny on Little Piney Creek, just east of the Bighorn Mountains in contemporary north-central Wyoming, where the Army was tasked to guard the Bozeman trail to the Montana gold fields. Red Cloud had laid the ambush. Crazy Horse acted as the stalker, taunting the soldiers, baring his rear end and daring them to come ahead. When they did, they were subject to an onslaught of 40,000 arrows, 1,000 for every minute of the fight. The bodies of the troopers and their four officers were mutilated after death, which to the Indian’s way of thinking hampered their passing to the Sacred Hunting Ground. The half-starved troops and civilians inside the fort heard the fight, but it was over too quickly for a rescue outfit to join the fray.

Red Cloud lived to the age of 88 and died on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota where his descendants still live. He is buried in a cemetery atop a hill on the reservation, from where one can almost see the Black Hills, the sacred Paha Sapa, taken (another broken treaty) from the Indians when gold was discovered there in 1874. Red Cloud knew the Whites—he visited Washington many times and he’d seen their world. He understood.

At the end of his life he said, “The white man made me a lot of promises, and they only kept one. They promised to take my land, and they took it.”