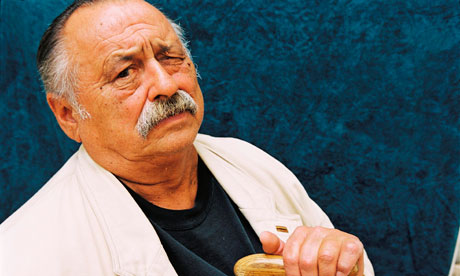

Jim Harrison. Songs of Unreason, Copper Canyon Press (143pp. $22)

Jim Harrison. Songs of Unreason, Copper Canyon Press (143pp. $22)

My friend Arlice Davenport is the book editor of the Wichita Eagle. He’s a perceptive traveler, philosopher and poetry lover. He wrote this appreciative review of Jim Harrison’s latest volume of poetry. I know he wouldn’t mind me sharing it with you:

Nature nurtures the poet’s soul with ineffable longing. The world indwells him, engulfs him, immerses him in the endless river of time. He struggles to rise above it, to sing its rhythms. But the world is not word. It overflows; it does not mean. So the poet indwells the poem, searching for the hidden source of song and soul, searching for the place where world and word become one. Jim Harrison has found the source.

Now well into his 70s and staring down mortality with his one good eye, Harrison has written a nearly pitch-perfect book of poems, shining with the elemental force of Neruda’s “Odes” or Matisse’s paper cutouts. His is an old man’s voice, seasoned and crusty, confident and fierce, bearing the world’s wounds as hard-fought medals of honor.

His heart proves equal to anything that nature throws his way: fire and water, stone and ice. But always the river calls him back, churning, distilling, spawning his song. In “Songs of Unreason”, his finest book of verse, Harrison has stripped his voice to the bare essentials—to what must be said, and only what must be said. He has mined the decades of his prolific, voluminous prose—much beloved and celebrated—as a long apprenticeship in a single direction: toward this culmination of vision and vitality; toward this testament of devotion and faith in the ageless power of the Earth. He sings of man and dogs wandering the mountains of Montana or the deserts of Arizona in wonderment at the great gift of being that is the world, that is word and soul. That is his life.

Tiring of language, the mind takes flight/swimming off into the ocean of air thinking/who am I that the gods and men have disappointed me? (From “Bird’s Eye View”)

Over the past century, poetry has metamorphosed into ever shifting shapes, never stable, sometimes street-smart, seeking praise for broken prose. What makes a poem a poem? Plato thought it a kind of madness, irrational and deadly, and banished poets from his republic. Harrison counters: “ a bone-deep language/without nouns and verbs”; a “music/well before the words occur.” For both, poetry springs from human wildness, the sudden thunderstorm in the desert, icy swirls of mountain snowmelt. Call it speech beyond words, part embodiment, part ghost. When poetry descends to this mute essence, for Harrison, it always arises as music that baptizes and restores: “We were born to be moving water not ice.” This motion, this straining toward what is there, other than oneself, powers his poems with a haunting pathos—a regret for what is lost, a longing for what lingers.

Winding through this gem of a book is “The Suite of Unreason”, a long poem composed of short stanzas printed in sans-serif type on unnumbered pages, each enigmatic fragment facing a longer, titled poem. The effect is mesmerizing and mysterious. In the counterpoint of poem on poem, Harrison’s mythic imagination thrives: surreal, yet carefully controlled, spilling over into the unforced grace of dreams.

For Harrison, it is the image, not the word that calls deep to deep; it is the image that evokes and connects the poet and the poem—reader too—with the inky pools of the collective unconscious. The image bridges the gap between world and word, song and soul. Without it, they remain isolated and alienated; with it, their mutual mystery blooms. “Songs of Unreason” soars as a triumph of atavistic imagism, making Harrison one of the last great romantics of American art.

Hear him on death, as he sounds the depths of unreason:

it’s mostly a placid

lake at dawn, mist rising,

a solitary loon

call, and staring into the still,

opaque water

Speech beyond words, river of life. These are songs of the soul that all of us can sing.