Edward Hoagland. Sex and the River Styx, Chelsea Green Publishing, Vermont (272 pp. $$17.95)

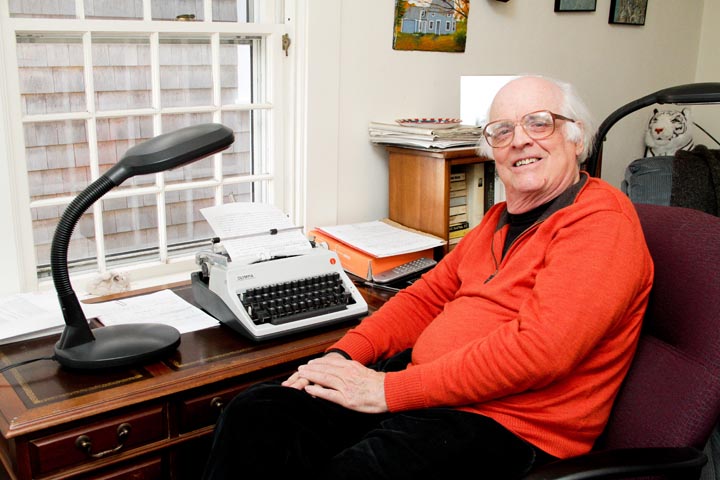

Edward Hoagland is one of my favorite writers and a beloved figure in American letters. He is my review of one of his latest books.

Biologists worldwide warn that we are entering a sixth great extinction event. Songbirds are dying off, the great mammals are disappearing, as are forests, frogs and fishes of the sea, victims of human expansion, habitat destruction, climate change and the economics of grown. In “Sex and the River Styx” Edward Hoagland, America’s greatest essayist and nature writer (our 21st century equivalent of John Muir) ruminates not only on the luminous wealth of nature and its gradual diminishment, but also on his own mortality.

Hoagland (author of the immortal “Notes from the Century Before”) is, like Jim Harrison, Joan Didion and John McPhee, a national treasure. And, at age 78, he can sense the end of his life. But the smell of death in the air, the aura of massive extinction to come, the blinding white brilliance of cities that obliterates constellations and the night itself—none of these, nor any sense of foreboding about the future can overwhelm this man’s exalted love, a love that extends not only to the glorious web of nature, but also to his fellow man.

“Sex and the River Styx” is a series of 13 linked essays exploring such subjects as Hoagland’s rural Connecticut childhood, working with elephants in the Ringling Brothers circus during the early 1950s, the traditions of American political dissent, and travels in such places as Vermont and on the African veldt. Hoagland describes driving a rattling Model A across America on Route 66, with only a “twenty dollar bill tucked in my shoe for emergencies.”

Other topics include Tibetan barley and yaks, becoming a “codger”, marriage, and always, his beloved Africa, where he seems most at home, especially among the “shattered” wild herds on a continent which Hoagland describes as a “crucible of mayhem, torture and murder”. Gone are the African days when on the vast plains of East Africa “pristine herds browsed among the thorn trees as creatures do when engaged in being themselves.”

Yet, despite Hoagland’s obvious passion for elephants, lions and reptiles large and small, he reserves a special love for humans and cities: Two essays in particular concern his life-long affair with New York City and its people. And in “A Last Look Around,”

Hoagland writes passionately about the 2 million people who have died in southern Sudan during decades-long fighting. In “Visiting Noah”, Hoagland describes a visit to a Ugandan family to whom he’s been sending $20 dollar bills slipped “into a greeting card so they wouldn’t show through the envelope if a larcenous clerk were looking for them.”

It is this theme that is most fundamental: How to remain human and loving in an era when “not just honeybees and chimpanzees are disappearing, but incomprehensibly innumerable species that have never been discovered at all.”

The drawbacks of the book are few: In my copy attributions to the magazines and journals in which articles first appeared were missing. The volume could have used some illustrations, and perhaps a photograph or drawing here and there, just to enhance the presentation. However, these technical faults are negligible. The book is a treasure.

And what of death? How hard will it be to leave the earth whose beauty is fading and whose mystery is dispersed? Hoagland writes: “….accepting death as a process of disassembly in humus, then brook, and finally seawater demystifies it for me. I don’t mean I comprehend bidding consciousness goodbye. But I love the rich smell of humus, of true woods and soil, and of course, the sea—long rivulets and brooks, lying earthbound on the ground. The question of decomposition is not pressing or frightening. From the top of the food chain I’ll re-enter the bottom. Be a bug; then a shiner shimmering on the closest stream…or partially mineralized—does one need a hippocampus? A green shoot a woodchuck might eat seems okay. I believe in continuity through conductivity: that the seething underpinnings of life’s flash and filigree may appear temporarily dead, but may spark across a species like the electricity of empathy, or as through paralleling the posthumous alchemy of art.”

In other words, the starlight that made us shines on in cosmically infinite forms. Who needs a hippocampus, indeed?