Turner, Frederick. Renegade: Henry Miller and the Making of ‘Tropic of Cancer’, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2012 (244pp.$24.95)

Franz Kafka’s maxim that a book should be an ax to the soul applies in spades to Henry Miller’s masterpiece, “Tropic of Cancer,” published fifty years ago in the United States by Grove Press. Miller’s sexual adventurism, anti-Semitism and misogyny aside, this “great blob of spit in the eye” (as the author himself called it) marked the emergence from obscurity of a writer so intense, so brilliant and so outré, that he compares favorably with Marlowe and Shakespeare in his ability to sustain a monologue. Norman Mailer, another writer known for gangsterism in literature, pronounced himself taken aback by Miller’s artistic audacity “Tropic of Cancer” stands with “Huckleberry Finn” and “Absalom, Absalom” (with “A Farewell to Arms” close by) as the enduring classics of American literature.

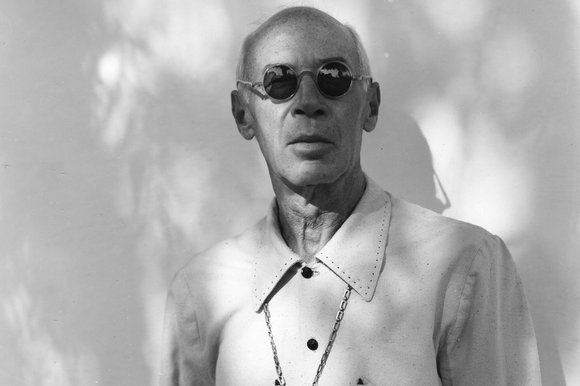

It is hard to imagine that anyone could tell the story of Miller’s road to the Tropics any better than Frederick Turner in Yale University’s Icons of America series. “Renegade” is very much more than a re-telling of what is known of Miller’s life his wretched street life in Brooklyn at the turn of the century, his bohemian search to avoid bourgeois existence, and the sudden fateful meeting with his negative muse, the beautiful, alluring and mentally unstable June Mansfield (one last name among many she used) somewhere around 1922.

Turner’s writing stunningly fans the flames of Miller’s own path toward an art which transformed flagrant philandering, maudlin suffering, deep humiliation and loneliness into a career dominated by the single-minded pursuit of spiritual truth. In Turner’s skillful hands Miller’s story comes blazingly alive. Miller escapes his father’s tailor shop in Brooklyn to become a wandering autodidact with a satchel full of awful writing in pre-World War I America. He pimps for his wife, who finally sends him to Paris to be rid of his pestering, and complaints about art. Alone on the streets, almost penniless and without any French, Miller not only survives but creates a legend and publishes, supported by friend Anais Nin, with Obelisk Press in 1934, a book so unusual that it astounds not only Paris, but London and New York as well. And exactly how would an American expatriate in depression-era Paris write a book that told the truth? Miller had already rejected so-called realism (Crane, Dreiser) and the European masers (Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Mann). What was left?

Rising from his pre-artistic paralysis, Miller began to wander the Paris streets taking notes, writing letters bristling with arcana, autobiographical excursions, slabs hacked out of other books he’d come across, newspaper articles, observations about people, his needs, his raw yearning and aspirations. He talked endlessly, cadged drinks and suppers, and wandered among the Apaches, Parisian petty criminals and pickpockets. He rejected plot and, eventually, most of narrative itself. The book he wrote became Henry Miller. Famously, he found himself along and penniless, “the happiest man alive.”

“Tropic of Cancer” shocked many people when it was published. Government authorities in the United States fought to suppress it. It was, of course, language that gave the greatest offense, the raw obscenity of the thing itself which, along with its cruel, open-eyed humor, its rank bigotry, and its unvarnished hope, that throttled the unsuspecting reader. Miller writes, “One is ejected into the world like a dirty little mummy…all the roads are slippery with blood and no one knows why it should be so.” All of this because we refuse to come to terms with existence, birth, toil, suffering, aging, loss and death. For Miller, these fundamental conditions cannot be changed. But what can be altered is our attitude toward life. The miracle for Miller is that some “men have created roses out of this dung heap” and that they “should want roses.” Another miracle is this short book by Frederick Turner in the Yale Icons of America Series.