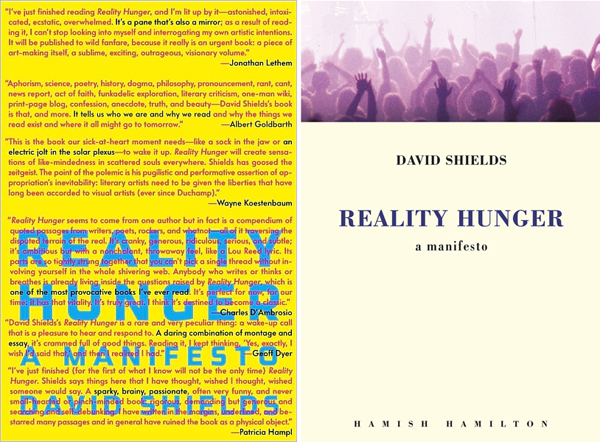

Perspectives: Reality Hunger: A Manifesto, by David Shields, Alfred A. Knopf, New York (2010)

We must accept the premise, so important to David Shields, that our society and culture now is “unbearably manufactured”, riddled with spectacle, innuendo, falsehood, celebrity, misinformation and data smog. “Reality TV dominates broadband, YouTube and Facebook dominate the web”, “realities” that already obliterate a culture obsessed with “reality” in which individuals qua individuals “experience hardly any” reality at all. Screen zombies everywhere, children of postmodern modes. The problem for the artist who wants to infuse his/her work with reality is how to “smuggle” it inside the thing. What form should reality take in postmodern art? How can a writer compete with digital media, sonic booms from ghosts who wear corporate sheets and scare the shit out of everybody? Shields’ book argues against plot, narrative, foreshadowing, linear drive—everything that the nineteenth and twentieth century novel stood for in its heyday; instead, he’s for cutting and pasting, montage, pastiche, memoir, autobiography, and ultimately, the extremely personal lyric essay. Shields favors any form devoted to exposing the self in radical ways, forms that explode the novel, the long short story, whatever writing that devotes itself not to developing a “certified” narrative (beginning, middle, end, characters, dialogue, imaginary shapes as a simulacrum of the real world) but to exploring randomness, accident, identity, spontaneity, emotional urgency, nakedness. His book is aphoristic—he “steals” from major writers, thinkers and artists, living up to his word. He begins in the beginning—writing as “list making and account-keeping” and ends with Frey’s “lies” on Oprah. Love it or hate it, “Reality Hunger” astounds. Shields manifesto argues that the lyric essay is, for better or worse, the best form to grapple with American reality.

Unfortunately—seriously unfortunately, Shields is a follower of the by-now infamous John D’Agata of the Nonfiction Writing Program at the University of Iowa, whose controversial argument about “fact” and “nonfiction” first arose in the context of a book that D’Agata wrote called “Lifespan of a Fact” which itself was fact-checked by an editor at The Beliver. The piece was ostensibly about the suicide death of a Las Vegas 16-year old named Levi Presly who had jumped from the observation deck of the Stratosphere Hotel, D’Agata using the death as the fulcrum for a meditation on suicide, Las Vegas and other themes. Trouble arose when it turned out that D’Agata invented, massaged and generally mis-used many “facts”, turning them into something else again. When called to task by the fact-checker, a guy named Fingal, D’Agata turned his wrathful glare not on fact itself, but the hapless fact checker. He’d “taken liberties” he admitted. (Here, Fingal had found seven fabrications in the first sentence of the piece, alone.) Claiming the right of the “artist” to invent, D’Agata blasted the fact checker as ignorant, though his hostility actually went far through the roof, and in public too. D’Agata, has published three books at Greywold which claim to be “histories” of the essay. These are controversial to say the least and many people think them utter rubbish—academic postmodern gibberish, and wrong to boot. (See, eg. January/February The Atlantic, “In Defense of Facts” by William Deresiewicz)

The best antidote to reading David Shields is probably Montesquieu, maybe Orwell, or better yet, recent essay anthologies by Joyce Carol Oates or Philip Lopate. An essay is a form of “argument”, an argument from a premise to a conclusion that along the way may be imaginative, artistic, personal, meditative, and even dreamy. But, even if temporary and subject to revision, a fact is always a truth, whether scientific, historical or artistic, never something shoehorned into reality. We ignore them at our cultural and political peril.

(Think here about fascism: Beyond fact, faith in individuals instead of science or truth; the power of Will, denial of consistency; hope for the Power of one person, magical thinking, chants, slogans, misplaced faith—I alone am true.)

“When they were published, the books that now form the canon of Western literature (the Iliad, the Bible) were understood to be true accounts of actual events.”

“So secure was the preference for truth that Sir Philip Sidney had to fight, in Defense of Poesie (published after his death in 1595), for the right to” lie” in literature.”

“The origin of the novel lies in its pretense of actuality.”

The word novel, when it entered the languages of Europe, had the vaguest of meanings; it meant the form of writing that was formless, that had no rules, that made up its own rules as it went along.”

“In the eighteenth century, Defoe, Richardson, and Fielding overthrew the aristocratic romance by writing fiction about a thief, a bed-hopper, and a hypocrite—novels featuring verisimilitude, the unfolding of individual experience over time, causality, and character development.”

“The novel has always been a mixed form; that’s why it was called novel in the first place. A great deal of realistic documentary, some history, some topographical writing, some barely disguised autobiography have always been part of the novel, from Defoe through Flaubert and Dickens. It was Henry James (especially in his correspondence with H.G. Wells) who tried to assert that the novel, as an “art form”, must be the work of the imagination alone, and who was responsible for much of the modernist purifying of the novel’s mongrel tradition.” “I see writers like Naipaul and Sebald making a necessary postmodernist return to the roots of the novel as an essentially Creole form, in which “nonfiction” material is ordered, shaped, and imagined as “fiction”. Books like these restore the novelty of the novel, with its ambiguous straddling of verifiable and imaginary facts, and restore the sense of readerly danger that one enjoys in reading Moll Flanders or Clarissa or Tom Jones or Vanity Fair—that tightrope walk along the margin between newspaper report and poetic vision.”

“In the first half of the nineteenth century, which remains for many a paradise lost of the novel, certain important certainties were in circulation; in particular the confidence in a logic of things that was just and universal.”

“The author has not given his effort here the benefit of in knowing whether it is history, autobiography, gazetteer, or fantasy,” said the New York Globe in 1851 about Moby Dick.”

“In the second half of the nineteenth century, several technologies emerged…Broadcast media—first radio, then television—homogenized culture even more. TV defined the mainstream. The power of electromagnetic waves is that they spread in all directions, especially for free. Plot itself ceased to constitute the armature of narrative. The demands of the anecdote were doubtless less constraining for Proust than for Flaubert, for Faulkner than for Proust, for Beckett than for Faulkner. To tell a story became strictly impossible.”

“The American writer has his hands full, trying to understand and then describe and then make credible much of American reality. It stupefies, it sickens, it infuriates, and finally it is even a kind of embarrassment to one’s own meager imagination. The actuality is continually outdoing our talents, and the culture tosses up figures almost daily that are the envy of any novelist.”

“What is a fact? What’s a lie, for that matter? What, exactly, constitutes an essay or a story or a poem or even an experience? What happens when we can no longer free the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience?”

“Living as we perforce do in a manufactured and artificial world, we yearn for the “real”, semblances of the real. We want to post for something nonfictional against all the fabrication—autobiographical frissons or framed or filmed or caught moments that, in their seeming unrehearsedness , possess at least the possibility of breaking through the clutter. More invention, more fabrication isn’t going to do this. I doubt very much that I’m the only person who’s finding it more and more difficult to read or write novels.”

“Conventional fiction teaches the reader that life is a coherent, fathomable whole that concludes in neatly wrapped-up revelation. Life, though—standing on a street corner, channel surfing, trying to navigate the web or a declining relationship, hearing that a close friend died last night—flies at us in bright splinters.”

“The merit of style exists precisely in that it delivers the greatest number of ideas in a fewest number of words.”

“The right voice can reveal what it’s like to be thinking: the inner life in its historical moment.”

“We don’t come to thoughts; they come to us.”

“Plot isn’t a tool; intelligence is.”

In Shields’ book, few of these aphorisms, sayings, and quotes belong to him. They’re stolen, appropriated, altered (some of them). Emerson, Anne Carson, David Foster Wallace, Heidegger etc.He has not written an essay, but appropriated a non-form for purposes of piracy, truthiness as chatty academic crap.