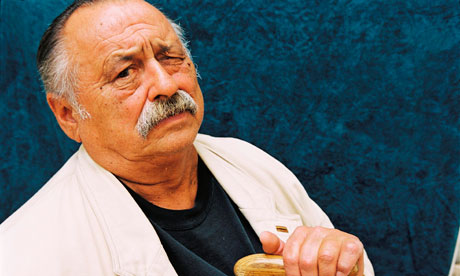

Jim Harrison died last Saturday at his cabin outside Patagonia, Arizona. He’d been at a cowboy saloon earlier, drank some vodka, talked to some pals, and went home. He was found later at home, dead of a heart attack. He was one of my constant heroes. I’ve followed his career, reviewed his books for the local newspaper, and collected, or tried to, everything he published. He wanted since 14 to be a poet. He became one and unearthed some scorching truths along the way. I just finished his last novel two days ago–“The Last Minstrel”. Here is an excerpt from an important part of it, about the writing life. So long, Mr. Harrison. See ya.

The Writing Life: Jim Harrison, “The Ancient Minstrel”

Passacaglia for Staying Lost, an Epilogue

Often we are utterly inert before the mysteries of our lives, why we are where we are, and the precise nature of the journey that brought us to the present. This is not surprising as most lives are too uneventful to be clearly recalled or they are embellished with events that are fibs to the one who owns the life. A few weeks ago I found a quote on my bedside journal, obviously tinged with night herself, saying, “We all live on death row in cells of our own devising.” Some would object, blaming the world for their pathetic condition. “We are born free, but are everywhere in chains.” I don’t believe I ever felt like a victim and so prefer the idea that we write our own screenplays. The form or genre of the screenplay is too severely compromised for honest results. You are obligated to write scenes that people will want to see, and “Jim, head in hand, spent an entire three days thinking” won’t work. It’s on the order of the oft-repeated slogan of the stupid, “I don’t know much but I know what I think.” Many years ago when I flunked out of graduate school, it occurred to me that the cause of this outrageous pratfall was the personality I had built. It all started when I decided at age fourteen to spend my life as a poet. There weren’t any living examples in northern Michigan so I gathered what information I could, mostly fictional, and usually painters. Painters’ lives can be fascinating, poets’ less so. But both were at the top of the arts list. If I was tempestuous and living in a garret in New York or Paris I would look better with smears of paint on my rugged clothing than lint or dandruff. So I read dozens of books on poets and painters to give me hints on what kind of personality I should have. I even painted for nearly a year to add to the verisimilitude. I was a terrible painter; totally without talent, but I was arrogant, captious, and crazy so I convinced friends I was indeed an artist.

The “everything is permitted” confusion has pretty much lasted my entire life. Of course it’s nonsense, but then the ego is beleaguered without its invented fuel and ammunition. You can’t squeak out like a mouse that you’re a poet, or walk in the mincing steps of a Japanese prostitute. Part of the trouble is that you are liable to think of yourself as a poet long before you write anything worth reading and you have to keep this ego balloon up in the air with your imagination. I survived on both good and very bad advice. Doubtless, the best is Rilke’s “Letters to a Young Poet” and possibly the worst, which I religiously adhered to, was that of Arthur Rimbaud who advised to imagine your vowels had colors and for you to go through the complete disordering of your senses, which is to say you should become crazy. I managed quite easily. This was mostly to advise young poets not to become bourgeois. Even conservative old Yeats said that the hearth is more dangerous than alcohol.

All over America young people are going to bad writers for good advice. There are so many MFA programs in the colleges and there are not enough good writers around to teach in them. As opposed to what you might think, teaching is brutally hard work if you insist on doing a good job. And your own work is liable to suffer.

Money is a vicious whirl, a trap you are unlikely to lie through in a healthy way.

In a lifetime of walking in the woods, plains, gullies, mountains I have found that the body has no more vulnerable sense than being lost. I don’t mean dangerously lost where my life was in peril but totally misdirected knowing there was a lifesaving log nine miles to the north. If you’re already tired you don’t want to walk the nine miles, much of in the dark. If you run into a tree it doesn’t move. I usually have a compass, also the sun or moon or stars. It’s happened enough that I don’t panic. I feel absolutely vulnerable and recognize it’s the best state of mind for a writer whether in the woods or the studio. Your mind feels a rush of images and Ideas. You have acquired humility by accident.

Feeling bright-eyed, confident, and arrogant doesn’t do this job unless you’re writing the memoir of a narcissist. You are far better being lost in your work and writing over your head. You don’t know where you are as a point of view unless you go beyond yourself. It has been said that there is an intense similarity in people’s biographies. It’s our dreams and visions that separate us. You don’t want to be writing unless you give your life to it. You should make a practice of avoiding all affiliations that might distract you. After fifty-five years of marriage it might occur to you it was the best idea of a lifetime. The sanity of a good marriage will enable you to get your work done.

James Douglass

May 1, 2016 -

Thank you for this post.

Just finished your review of John Gillette’s “Elephant Complex” in the Sunday Eagle (May 1, 2016) and wandered over….