Michael Herr died last June 23, 2016, a sad day. Herr’s book “Dispatches” was the only true news from the war I remember. I was subject to the draft during the War, fought not in Vietnam but in the streets of the United States, and read his book on its publication. It had a profound effect on me. Surreal, real, full of music, violence and dark poetry, it is a book for the ages. “Dispatches” should be required reading for all those ready to head off to war at the drop of a hat. Here is the obituary published in the June 25, 2016 New York Times. For those truly interested, access a Terry Gross (“Fresh Air”) interview with Herr that was re-broadcast just after his death. It is a revelation:

Michael Herr, who wrote “Dispatches,” a glaringly intense, personal account of being a correspondent in Vietnam that is widely viewed as one of the most visceral and persuasive depictions of the unearthly experience of war, died on Thursday at a hospital near his home in Delaware County, N.Y. He was 76. His daughter Claudia confirmed the death, saying he had been ill but not specifying the cause.

The war in Vietnam and its dehumanizing effect on its participants figured widely in Mr. Herr’s writing life. He contributed the narration to “Apocalypse Now,” Francis Ford Coppola’s epic adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness,” and with the director Stanley Kubrick and Gustav Hasford wrote the screenplay for “Full Metal Jacket” (1987), adapted from Mr. Hasford’s novel (“The Short-Timers”). But it was “Dispatches” that declared Mr. Herr’s unimpeachable credentials as a witness to the fearsome fury of combat and, perhaps more terrible, the crippling apprehension that precedes it. “You could be in the most protected space in Vietnam and still know that your safety was provisional, that early death, blindness, loss of legs, arms or balls, major and lasting disfigurement — the whole rotten deal — could come in on the freaky-fluky as easily as in the so-called expected ways,” he wrote, “you heard so many of these stories it was a wonder anyone was left alive to die in firefights and mortar-rocket attacks.” He went on: “Fear and motion, fear and standstill, no preferred cut there. No way even to be clear about which was really worse, the wait or the delivery.” Published in 1977, almost a decade after his yearlong sojourn in Vietnam and after he had recovered from his own bout of depression brought on by his war experience, the book was a sensation, an acutely observed, acutely felt, wisely interpretative travelogue of hell, deeply sympathetic to the young American conscripts, and deeply skeptical of the political and military powers that kept them there.

Written with the residual rhythms of the 1960s counterculture, redolent of drugs and rock ’n’ roll, it was also partly fictionalized, though its authenticity was received by critics — and ordinary readers — as indisputable, and they treated it as an exemplar of the kind of fiction that is truer than fact. In a front-cover review in The New York Times Book Review, C .D. B. Bryan, the author of “Friendly Fire,” the account of a soldier’s death in Vietnam and its aftermath, declared, “Quite simply, ‘Dispatches’ is the best book to have been written about the Vietnam War.” The novelist John le Carré described it as “the best book I have ever read on men and war in our time.”

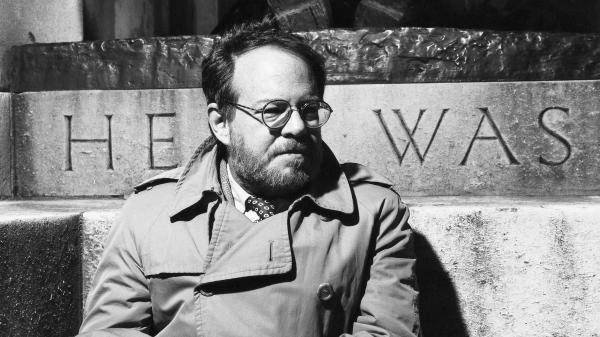

In an interview on Thursday, the novelist Richard Ford, who was a friend of Mr. Herr’s, said: “‘Dispatches’ gave an emotional, verbal and aural account of the war for a whole generation — of which I am a member — particularly for those who didn’t go. His nose was right in the middle of it, and he wrote exactly what it was like to be in that place and to be that young.” “Dispatches,” Mr. Herr’s account of his time in Vietnam, was published in 1977. Credit Tony Cenicola/The New York Times

Michael David Herr (pronounced hair) was born on April 13, 1940, in Lexington, Ky. He was still an infant when his parents, Donald Herr and the former Muriel Jacobs, moved the family to Syracuse, where the father ran a series of businesses in the area. After high school, Michael went to Syracuse University but, aspiring to Hemingwayesque adventures and literary achievements, he dropped out to travel in Europe and write. He served in the Army Reserve, reportedly to avoid the draft, and wrote for publications including The New Leader and Holiday. Late in 1967, he persuaded the editor of Esquire, Harold Hayes, to send him to Vietnam. It was shortly before the siege of Khe Sanh, one of the war’s bloodiest battles, and the Tet offensive, a widespread North Vietnamese campaign against targets in the South. Writing for a monthly magazine, Mr. Herr was an oddity in the press corps; one soldier asked if he would be reporting about what they were wearing, and the American commander, Gen. William C. Westmoreland, wondered if his assignment was to produce articles that were “humoristic.” But the anomalous nature of the job worked to his advantage. Traveling without restrictions, essentially embedded (as the term later came to be understood) with soldiers wherever he wanted to go, he produced a handful of vivid pieces for Esquire in the year or so he spent in country. (Hayes apparently didn’t expect even that. “I got him a visa and advanced him $500, then forgot about him,” he recalled in a history of the magazine, “It Wasn’t Pretty Folks, But Didn’t We Have Fun?,” by Carol Polsgrove). Then he spent the next 18 months in New York working on the book before his experiences in Vietnam caught up with him.

“I flipped out,” he recalled in an interview with The Los Angeles Times in 1990. “I experienced a massive physical and psychological collapse. I crashed. I wasn’t high anymore. And when that started to happen, other things started to happen, too; other dark things that I had been either working too hard or playing too hard to avoid just became unavoidable.”

In addition to his daughter Claudia, who is an editor at Penguin Random House, Mr. Herr is survived by his wife, the former Valerie Elliott, whom he married in 1977; another daughter, Catherine Herr; a brother, Steven; and a sister, Judy Bleyer. Mr. Herr lived for many years in England, where he grew to know Stanley Kubrick and eventually wrote a book about their friendship and collaboration. His other work includes a fictionalized biography of the gossip columnist Walter Winchell, a strange hybrid that is part novel, part screenplay.