Labor, Earle. Jack London: An American Life, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2013 (461pp. $30)

At the height of his fame in the early 1900’s, Jack London was earning ten thousand dollars a month from a variety of sources including royalties on his novels and non-fiction works, magazine serials and articles, journalism assignments and speaking engagements. He could have earned much more had he not been so roundly cheated at business, had he not been so profligate, and had foreign publishers not pirated his works freely as was the custom then. A member of the Socialist Party and an avowed advocate for the rights of working people, he lived high on the hog, building himself a luxury yacht aboard which he intended to sail around the world (he made it as far as the Solomon Islands) and erecting for himself and his wife a Xanadu-style stone mansion in Glen Ellen, California which burned to the ground before it could be inhabited, melting both the gold-plated bathroom fixtures and London’s own outlandish dreams.

He was always dead broke, on the run from creditors far and wide, borrowing money from his publisher against his future earnings, supporting his ex-wife, his two children, his mother and her sister, buying drinks for everyone in the saloon. Never failing to write at least one thousand words each morning after breakfast, he published in one-or-another of hundreds of national magazines an amazing amount of tripe, fluff, balderdash, dreck and hack-work, as well as two world-famous novels, a handful of unforgettable stories and a couple of tracts about the Poor and Downtrodden which would become classics, paving the way for Orwell and The New Journalism.

Earle Labor’s new book about London, subtitled “An American Life”, is an obvious labor of love (no pun intended). As curator of the Jack London Museum and Research Center in Shreveport and Emeritus Professor of American Literature at Centenary College of Louisiana, Labor is the acknowledged national authority on the life and work of London. Labor’s work was graced by personal friendships with London’s two daughters, Joan and Becky, as well as his own discovery of Charmian London’s personal diaries in a safe at the “Cottage” in Sonoma, diaries that London’s wife herself called “disloyal” because of their intimate frankness. To these new sources were added a number of previously undiscovered London letters and discussions with the descendants of London’s bohemian friends in the Bay Area.

Abandoned by his father, Jack London grew up in poverty and was sent to work in the “pit” (as he called it) as a boy, an experience that, like Dickens before him, turned him against the bosses and set his mind on fire. Before age fifteen he’d become an Oyster Pirate on San Francisco Bay, stealing the delicacies owned by Railroad Monopolies before they could reach the plates of the rich. He joined the Fish Patrol at sixteen, journeyed as a cabin boy to Siberia to kill seals at seventeen, enrolled and left high school in Oakland, set pins in a bowling alley, and began to write, sending stories out to magazines at an amazing clip. He sold a few and was encouraged. Then, he sold one to the famous “Atlantic Monthly” and he was on his way.

His faults were many and Labor a sets out to “neither maximize nor minimize” them, but only to accept London on his own terms as a natural born seeker, a gifted artist of exceptional intelligence, sensitivity and personal charisma, a man driven by a Nietzschean outlook on life at a time when literature was stuck between Victorian romanticism and the Modernism that wouldn’t be born until after the War. Given that, we are saddled with an artist who was at times a drunken sorehead, a philanderer and occasional fool, but also a great friend, world traveler and visionary, who bore up under the burden of numerous illnesses and diseases with amazing patience. He loved his wife deeply except when he was with another woman.

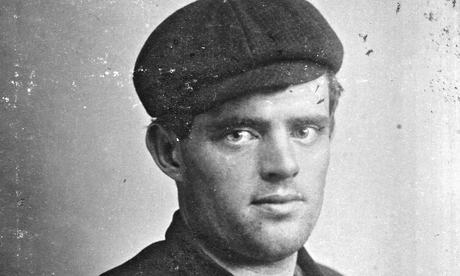

On Sunday October 22, 1905, London was in Lawrence, Kansas to deliver a lecture titled “Revolution” to five hundred students and guests at the University Auditorium. The Kansas City Star reporter present at the scene acknowledged London’s compassion and humor. “Occasionally he drew a laugh from his audience; once or twice when he talked about the child labor of the Southern States a woman wept quietly. He is like his published portraits vitalized,” she wrote. “Personally he has great charm of manner. He is very youthful, ingenuous and friendly.”

Sadly, London died at age 40 from alcoholism and kidney failure. But like London’s lecture that faraway autumn, Labor’s book recalls the man himself with great charm of manner.