Wade Davis is the current National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence. But he’s much more than that! Ethnologist, botanist, eco-traveler, master historian—and a writer whose prose glows, that’s Wade Davis. Here’s a review of his masterwork of mountaineering, the human soul, and World War I.

Davis, Wade. Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory and the Conquest of Everest, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2011 (655 pp. $32.50)

As the Great War drew to a close, a young English woman named Nancy Cooper wrote wearily in her diary that, “By the end of 1916, every boy I had ever danced with was dead.” In fact an entire generation (and more) of English, French and German youth was gone, shredded by shrapnel, riddled by machine-gun bullets or burned and scarified by mustard gas, their body parts scattered across the fields of the Somme, or Paschendale in Belgium, where they mixed with oozing mud and rat excrement, and finally disappeared. Granite tombstones by the hundreds of thousands are memorials, not graves. Those who made it home did so missing arms and legs, or eyes, or with their lungs roasted or faces mangled horribly. And then there were the lucky few like young mountaineer George Mallory, who made it home to Cheshire with invisible wounds.

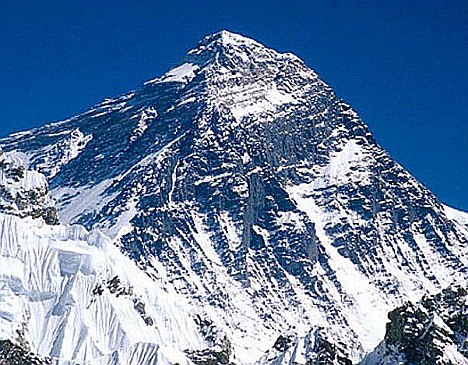

Master historian, ethnographer, and world-renowned eco-traveler, Wade Davis is the author of many acclaimed books about exploration and botany and he has written a genuinely gripping, thoroughly researched and beautifully illustrated book about the period 1921-24 which saw an intrepid group of British, Canadian and Australian war veterans set about to conquer, in a series of three dangerous expeditions, Mount Everest, then an unknown massif hovering menacingly, yet fascinatingly, on the border between Nepal and Tibet, territories which were themselves almost entirely unknown to the West.

“Into the Silence” begins where the Great War ends, when the last vestige of the Old Order was shattered, and death had made a mockery of notions like honor, valor and glory. Before the war, the Geographical Society in London, together with the Alpine Club, had upheld the British notion of empire by sending off its members to conquer peaks in the Alps in the name of English aristocracy. But the long hallucination of the war had produced a universal torpor and melancholy, a sense of isolation and a loss of center. The dozen or so young men who composed the British Empire’s expeditions to Everest in the early 1920s were as much a part of the Lost Generation as Hemingway and Fitzgerald. They climbed into a void in order to discover their souls and to escape the crushing boredom of bourgeois life.

“Into the Silence” was 10 years in the writing and is remarkable on many levels. It tells the story of courageous, bull-headed English climbers, men like Guy Bullock, the best alpinist of his day; Sandy Irvine, an accomplished rock climber who died on the shoulder of the North Col with Mallory in 1924; and the indomitable George Finch, the Alpine Club’s best rock climber and a man whose endurance matched and at times, overmatched, even Mallory’s.

These men, along with surveyors for the Raj, botanists, translators, and the elderly leader of the expedition, Gen. Charles Bruce, often camped at elevations as high as 22,000 ft., climbing higher with Sherpas and local Tibetans for guides. During the first expedition of 1921, seven Sherpas died at the base of Everest in an avalanche.

On another level, “Into the Silence” is a moving psychological romance. What, after all, would compel Mallory to climb up and beyond 26,000 feet in an era of hobnail boots and woolen vests, when the use of oxygen was both little known and mistrusted—while at home his wife and two small children waited with broken hearts? Davis answers the question masterfully by delving into war diaries, journals and regimental histories, each of which presents a clinical exposition of violence’s effect on the human mind.

And finally, “Into the Silence” opens a window onto little-known Tibetan history, topography, ethno-botany and religion. In those days, the British weren’t admitted to Nepal at all and their adventures in Tibet were usually highly restricted, frowned on by the Chinese—who coveted the Tibetan plateau (it is partly Britain’s fault that the Tibetans lost their independence)—and obviously observed jealously by an ever expanding Russia.

On the morning of June 8, 1924, Mallory and Irvine were camped at 27,000 feet, as exhausted as men in the trenches had been during the war. They were ready to go “over the top” (they might have said), though they were at war only with themselves and the mountains.

In 1999 a team of American climbers found Mallory’s body at the bottom of a sheer, 300-ft cliff of ice beneath the North Col and its final daunting shoulder. One leg had been broken in a long fall. Irvine was just gone, like so many before him on the Somme.

“Into the Silence” is a masterpiece standing atop its own world, along with the classic “Into Thin Air” by Jon Krakauer. Even the annotated bibliography that accompanies the text (with its many beautiful maps and old photographs) is a kind of masterpiece. As ridiculous as these old climbers were at times with their habits and “stiff upper lips” (Mallory for God’s sake smoked cigarettes as he camped in the heights), their radiance matches that of the peaks.