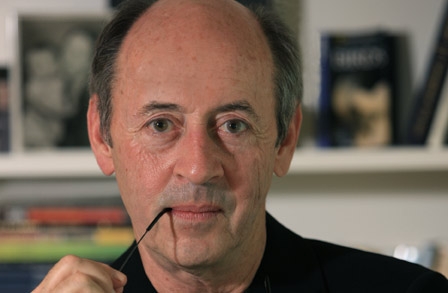

Billy Collins. Horoscopes for the Dead, Random House, New York, 2011 (106pp. $24)

It is hard to disagree with the New York Times that Billy Collins is “America’s most popular poet.” Having risen almost from thin air, he placed several books with university presses in the 1980s and then won the National Poetry Series. At that point, his books bega selling so well that earlier editions were reprinted. In 1997 his book “Picnic, Lightning” became a near best seller and Collins appeared with Garrison Keillor on NPR’s “A Prairie Home Companion”. Soon, he was a regular on the reading circuit, as well as on public radio’s “Writer’s Almanac” and “Fresh Air.” His role as Poet Laureate of the United States during 2001-06 increased his influence. His poems now reach a formidably large audience. The only American poets who’ve ever earned as much money lived in the 19th century.

Sadly, this collection is a dreadfully uneven work, full of bright moments and oddly moving pieces, as well as sullen failures, headlined by a few non-poems that scuttle like cockroaches across the kitchen floor. A particular example of the latter is a non-poem called “My Hero” which features a hare “zipping across the finish line” while the tortoise is “stopped once again by a bee humming in the heart of a wildflower.” While the tortoise may well be Collins’ hero in this non-poem, such musings hardly measure up to even high school sophomore-level English.

There is much to admire in “Horoscopes for the Dead,” however. Reading Collins is like sitting with a bright and affable companion who is not only a wonderful conversationalist but whose imagination is always at play. Twain said “You can’t depend on your eyes when your imagination is out of focus”, and the imaginative leaps he makes in a poem are the engines that drive them along. Take the poem “Thank-you Notes”, one of the best in the collection, in which the narrator begins with a scene from his childhood moves to passersby he saw today, then executes the surprising turn to “And while I’m at it / thanks to everyone who happened to die / on the same day I was born.” Going on, Collins expands the poem to explore the cycles of life and how we sense we “get out of the way” for the younger and youngest among us. But the tone of the poem is not direful. Instead, Collins allows us to feel joy at his surprising turnabouts. Other strong poems in the collection are “Two Creatures,” in which an owner observes his dog; “The Symbol,” a story of two mirrors in a barbershop; “Cemetery Ride”, in which the poet bicycles through a Florida graveyard; and, “Roses,” which is about, well, roses.

That said, many poems in the collection are poorly realized and just plain “thin.” Some poems like “Grave,” “Her,” and “A Question about Birds,” all deserve better endings, a turn poets call “putting the lid on the box”. A poem like “Girl,” in which the poet examines the drawing of a scallion made by, perhaps his daughter should have been excluded altogether from a serious book. However, this is the risk that a popular, conversational poet takes. Unlike the famous modernists (Eliot and Pound) who wanted their poems to be difficult and were writing for a small, select audience of intellectuals, Collins’ poems, perhaps more than those of anyone else in America, always invite us in to look around, invite us along for t heride.

Part of the happiness of his books is watching his mind at play. His poetry is like so much American poetry in the latter half of the 20th century in that, having been deprived by the modernist revolution of a sure sense of what poetic form should be, it increasingly turns to non-literary analogues like conversations, dreams, confessions and other kinds of discourse as substitutes for the ousted “fixed forms”. For example, one of Allen Ginsburg’s longest poems is called a “sutra”; William Stafford’s poetry is a mimesis of conversation; Gary Snyder probably invented the poem of instruction. Conversational poets like Collins are under a gun: be relaxed and brilliant at the same time. About the only way to be relaxed and brilliant at the same time is to execute an extended metaphor which his sustained and developed over a number of lines or, as in the case of “Poetry Workshop Held in a Former Cigar Factory in Key West,” through a whole poem. “For never in that sunny white building/ did I draw an analogy between cigar-making and poetry.”

And then, of course being the bright conversationalist, Collins does just that.