Davidson, Peter (ed.), George Orwell: Diaries, Liveright Publishing/W.W.Norton, New York, 2012 (597pp.$39.95)

One hundred million people died during the various ideological and political catastrophes of the 20th century—wars, famines and holocausts brought on by the tripartite clashing of imperial capitalist colonialism, nationalism, fascism and totalitarian communism. Perhaps no single person better observed these monumental disasters than George Orwell, born Eric Blair to a middling bourgeois father directly engaged in the official English opium trade conducted by the Indian civil service.Orwell died needlessly (the streptomycin that would have cured him was in short supply due to the war) of tuberculosis in January 1950, slightly more than two years after he published his fictional masterpiece, “1984”, a book which has now entered into immortality along with its author.

Renowned Orwell scholar Peter Davison has edited Orwell’s diaries into 11 subject matter subtitles, major parts o which have appeared in other places (“The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters”). In his guarded introduction to the “Diaries,” the late Christopher Hitchens observes that they “greatly enrich our understanding of how Orwell transmuted the raw material of everyday experiences into some of his best known novels and polemics.” Hitchens adds that many of the accounts of Orwell’s “interior” or “natural” observations present a more intimate picture of the man in his relationship to the wild, the rural and the remote. It is hard to agree with this generous assessment.

A decent argument could be made that the “Hop-Picking Diary” (1931), the “Road to Wigan Pier Diary” (1936), the “War-time Diary” (1940-41) and the extended “Jura Diaries” (1947-48) do what Hitchens claims. Unfortunately, some or all of these writings have also appeared elsewhere, or else were rendered into books so faithfully (with editing) that the diaries don’t extend our understanding of Orwell’s art, his writing processes, or his politics. The “Domestic Diaries”, which take up fully two-thirds of the book, involve what diaries often involve—observations about the weather, egg production from hens, wind direction, and cold. A typical entry from June 22, 1939: “Cold all day and very windy. Dense mist in the morning. Did nothing in the garden. 14 eggs.”

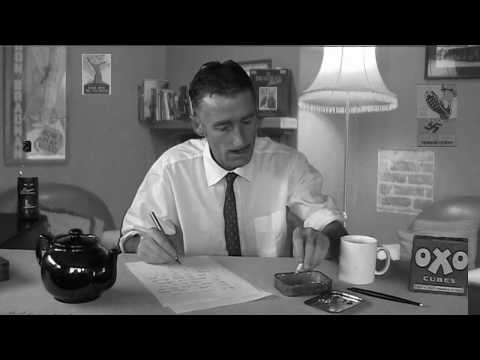

In truth, the real Orwell, like the real Kafka, is neither here nor there, neither in or out of the diaries. He is and he isn’t the man who bought 12 Moroccan hens on Oct. 12, 19389, and reports the first egg from these beautifies on Oct. 27. The net five diary entries record nothing but egg production. He is, of course, the man who wrote such classics as “Burmese Days,” “The Road to Wigan Pier,” “Down and Out in Paris and London,” and many astounding essays on politics and what are now called “cultural or critical studies”. Orwell was a socialist, an individualist and a truth seeker. He was abjured by the Right for his tilt toward “common goods”, and ridiculed by the Left when he broke with Stalin and the Popular Front after Spain was betrayed by communism during the Civil War. As a relentless opponent of nationalism and colonialism, he was accused of being anti-British, even though he staunchly supported the war effort and wrote strenuously in opposition to Hitler. His bitter denunciation of England’s India policy brought him nothing but pain from the government. As a writer, therefore, he found it hard to make a living: Thus, the necessity to worry about egg production from his beautiful Moroccan hens. A richer man—a politician or government leader, for example, would have flown to America for the antibiotics that might have saved his life. These days Big Lies conveyed to masses through the means of perfidious television screens by spin doctors have become part of our daily life. “Fair and balanced” now means “propagandistic and distorted,” just as in “1984” war meant peace. It was Orwell’s contribution to his own violent 20th century to draw attention to the dangers of abstractions like nationalism and race, to discount patriotism in favor of citizenship, and to write truthfully, as if our lives depended on it.

It is perhaps a good thing that these diaries are available for those who wish, as Hitchens says in his introduction, to “read with care.” Far better to read what Orwell published during his lifetime and leave egg gathering to that quiet, patient, committed man who nourished us with his work.