Brady, Frank, Endgame: Bobby Fisher’s Remarkable Rise and Fall (Crown Publishing Group, New York, 328pp, $25.99)

In the end he was alone, dying of a kidney disease for which he refused treatment by Reykjavik’s medical specialists, mistrusting doctors on principle and suspecting their motives. Years before he’d had all the fillings in his teeth removed, believing that the silver and mercury in his mouth might be a source of illness; now his teeth were falling out and those that remained were blackened with decay.

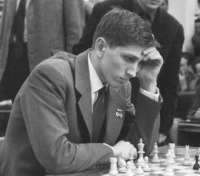

Gone, however, was Bobby Fischer, the American wunderkind who, for God’s sake, sat in front of the board squatting on a chair with two feet on its seat, whacking down rooks and pawns and knights with a hiss of Smack! Zap! Bobby somewhere down the road from 10 years old and already enjoying smiting his opponents as much as he despised losing.

Gone was that charming, irrepressible, gangly colt of a kid who became the youngest member of the stuffy Manhattan Chess Club, the boy who beat every senior master in sight, even drawing a game with Max Euwe, the former world champion. This was the child who learned rudimentary Russian and German in order to study the games of the world’s best chess players, emerging by 1956 at age 13 as the youngest chess master in U.S. history, a child with mentors, friends and admirers.

Long gone was Robert J. Fischer, grandmaster and world champion, envy of every chess player in the world, even those Soviet players who thought him wicked. Irretrievably lost were the games of luminous clarity, games so rational that they appeared crystalline, games whose brilliance were like diamonds, games that seemed fated by God to occur.

Gone was the world champion who won his title in Iceland during 1972’s nerve-racking match against Boris Spassky, even after Fischer had forfeited the first game and lost the second on a patzer’s blunder in the opening. After the match, Spassky left the Soviet Union, partly as a result of his profound loss to Fischer, considered a national disaster. Even Fischer knew that Fischer had gone, despite their sad rematch in Yugoslavia in 1992.

Frank Brady’s “Endgame” explores Fischer without judgment, to the extent possible. Born in 1943 to a nearly homeless single mother, Bobby experienced a lonely childhood until May 1949 when he learned chess from his sister Joan. He was immediately obsessed. In five years he was extraordinary; in 10 years, magnificent. His life was chess and only chess, and anyone who distracted him or failed to serve Bobby’s chess was a nobody, or worse.

Brady shows us Bobby’s first teacher, Carmine Nigro, and his first long-term mentor, Jack Collins, both eventually cast aside as Fischer’s paranoia inflated his mind and began to float away into anti-Semitism, hysterical egoism, and calculating narcissism. Brady shows us the tournaments, the travels and the lost years after the World Championship when he lived a rodent’s existence on skid row in L.A.

Robert Fischer eventually spent years with the Worldwide Church of God, Herbert W. Armstrong’s religious Ponzi scheme, donating thousands of dollars to its many operations, until drifting away from the church towards other towering fantasies of his own making. After he was indicted by the U.S. Government for violating sanctions against commercial dealings with Yugoslavia, Fischer lived in Hungary, Japan, the Philippines, and finally Iceland. He spit on the indictment (literally) and gloried in 9/11 as a curse on the Great Satan. The crackpot screeds and Jew-hating he spewed over a small Philippine radio station live forever on the Internet.

Brady is a seasoned biographer and knows his chess. he has told the story as well as he can tell it. For the general reader it is all there, fascinating in its outline and generous in its scope. And certainly as one of Fischer’s closest friends and advisers in the early, more rational years, Brady knows what there is to know.

But as a lover of chess and literature, I wish this story had been told by someone like Jon Krakauer, someone who could bring drama and tragedy to the table and discern its inner significance. I wish it had been told by John McPhee, the seasoned seizer of detail, a writer who could make Fischer live again between the lines.

And I wish the book had contained a thorough examination of the Fischer chess achievement in concrete detail, with tables of his results, perhaps an analysis of his style from a selection of his best games, with many more photographs on fine paper, with a truly monumental chess index and cross-index. I wish it had been 10 volumes. Perhaps Krakauer and McPhee, if you’re listening, you’ll team up and do it. Or perhaps I will do it myself.

In 1964 I played Bobby Fischer a game of chess. He appeared at Wichita State University, part of a nationwide tour, to give a lecture and to conduct a simultaneous exhibition. One of 44, I sat in awed silence as Fischer made his first move, P-K4. Did I play the Sicilian, Dragon Variation? Or the French? Or perhaps Fischer’s own variation of the Perc? Whatever, Fischer had me by the throat early on. By the fifteenth move I was lost, holding on for many more hopeless moves until the bitter end, just for the pleasure of being tortured by his exactitude. By then I was a nobody.

I remember Fischer well, tall, regal, dressed in a specially tailored brown suit, with expensive brown shoes. His lecture style was precise, dramatic, and incisive, in line with his reputation as an amazing analyst of the game.

His socks, however, were a mismatched blue.