Goldberger, Paul. Building Art: The Life and Work of Frank Gehry, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2015 (511pp.$35).

In his new book “Building Art”, author Paul Goldberger writes that world famous Los Angeles architect and designer Frank Gehry “almost never started a design with a predetermined shape.” Instead, Gehry began by “playing” (as he called it), with wooden blocks of different sizes, “each representing a portion” of a building’s functional program. “He would then stack or array the blocks in what he felt was both a practical and an aesthetically pleasing composition.” At full staff during the early 2000’s, Gehry’s Los Angeles office consisted of 150 or so architects, designers, and CATIA specialists (CIATA: specialized software programs for design), a staff that produced models from Gehry’s ideas. Gehry would review the models in the model shop, suggest tweaks, after which staff would produce a new model that incorporated his changes and the process would begin again. If this procedure sounds like the atelier of Titian or Rubens, then so be it. The title of Goldberger’s book suggests the truth of Gehry’s view: He was creating functional works of art–museums, apartment buildings, furniture, lamps, and homes that were intended to exhibit emotional depth through signature treatment.

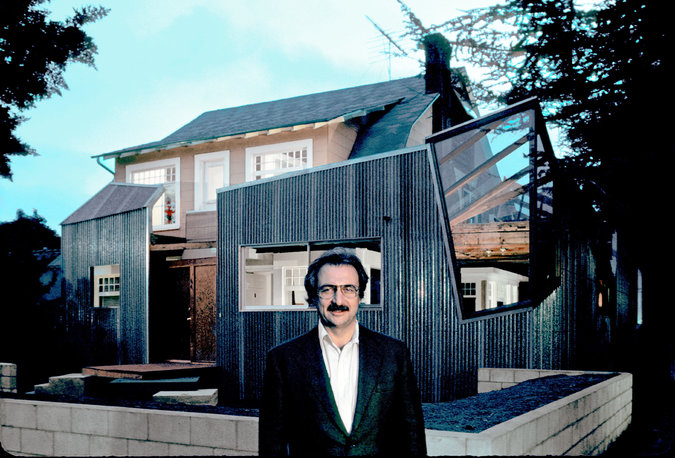

Gehry’s public projects are justly famous: The Walt Disney Concert Center in Los Angeles; the Fisher Center at Bard College; the ethereal and lionized Guggenhiem Bilbao on the Nervion River in Spain; the uniquely geometrical Museum of Biodiversity in Panama City; and most recently the ship-like and marginally controversial Fondation Louis Vuitton at the Jardin d’Acclimitation in Paris’ Bois de Boulogne, where rank commercial motives intersect with both art and its ultra-rich patrons—in all these projects Gehry had to walk the hot coals of public controversy hand-in-hand with wealthy guardians and sponsors. Early on, his work in Los Angeles tended more toward homes (Ron Davis House, 1972) or smaller public projects (Loyola Law School campus and central square (1979-94), and included his own Santa Monica home that upset his neighbors but has since become something of a landmark.

Goldberger, formerly architecture critic at the New York Times (where he won a Pulitzer Prize for architecture criticism), is a contributing editor at Vanity Fair and the author of many books, including “Why Architecture Matters”, “Reflections on the Age of Architecture” and “Up From Zero”. He also teaches at the New School and lectures widely on architecture, design, historic preservation and cities. “Building Art” is a densely structured work given over largely to the personal struggles and accomplishments of Gehry, who was born Frank Goldberg to middle class parents in Canada. When the family moved to Los Angeles in 1947, Gehry worked odd jobs, attended college, and found himself drawn to the artistic circles of Billy Al Bengston and Ed Ruscha. He was, for a long time, poor. And then he was rich and famous.

“Building Art” is highly readable, concentrating as it does on the celebrity of the architect and his struggles in the halls of power. Goldberger crams into his book all the “associations” Gehry built up over time—it reads like a compendium of movie stars, business moguls and government power brokers. Heads of State even make appearances front and center. And, for the first time, Gehry’s personal life spreads out before us like smog over Los Angeles—how he came to change his name, his ugly first divorce, and a maddening affair with the wife of a friend. To some extent, missing are the guts of the design struggle and the “hows” and “how-tos” of design itself, a lack that makes way for a popular biography accessible to a wide public.

Nevertheless, “Building Art” is a comprehensive and honest book, adroitly rendered and entertaining. Gehry himself has many champions and not a few detractors. This book gives them their due. Besides being beautifully made (it could use a few more photos and drawings), it will please readers everywhere who want to know what it is like to be a rich artist in the fast lane.