Thomas, Evan. Being Nixon: A Man Divided, Random House, New York, 2015 (619pp.$35)

When Nixon was at Whittier College, a small Quaker institution in southern California, he dated a stunner named Ola Florence, who was socially precocious and, in photos, looks pretty much sexually wiser than the straight-laced Nixon who was all about campus politics. One of Ola’s friends asked her how she could abide such a “stuffy” boyfriend. Ola replied that she thought “Dick was wonderful” because he was so “strong, so clever, so articulate.” Apparently he wrote her notes with “beautiful words and thoughts”. They were engaged for a time but there was no “hanky-panky.” After their relationship cooled, and Nixon had gone off to newly established Duke Law School on a scholarship, Ola recalled that Nixon dreamed of becoming chief Justice of the Supreme Court. “I always thought he’d achieve something extraordinary in life,” Ola told a biographer. She also admitted that she never really knew him because there was something hidden in his personality that she couldn’t penetrate.

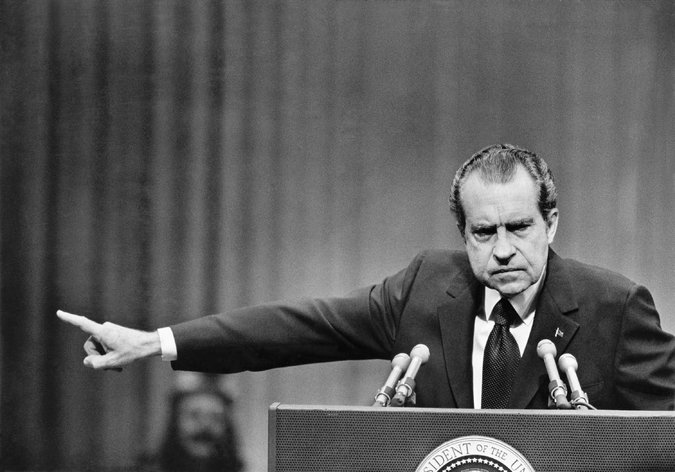

Having grown up the son of a Yorba Linda grocer and having felt the pangs of poverty, failure and insecurity, Nixon the man went on to be come the most powerful politician in the world. In Evan Thomas’ new book, “Being Nixon: A Man Divided”, the well-known path of Richard M. Nixon from big man on campus to frightened man in the White House to haunted ghost in Saddle River is fully, expertly documented. It is an American disaster story on many levels, one that most of us already know, but which fascinates nonetheless. Thomas, writer, correspondent, and once Washington Bureau chief for Newsweek, is a peerless researcher, professor of journalism at Harvard and Princeton, and the author of nine important books, some of which have been international bestsellers. Nixon, the subject of dozens of books, biographies, and studies, is hard to penetrate, even harder to elucidate. As much as anybody, Thomas has done the job.

Nixon was a very intelligent man, but possessed of neither perceptiveness nor imagination. He rejected out of hand self-examination as a sign of weakness, and when it got to be the “60s”, he hated the decade’s emphasis on inwardness as both prurient and sad. Thomas demonstrates confidently that Nixon justified his rejection of self-knowledge in favor of raw, unexamined emotionalism as a sign of strength, that his “weakness—that his sleeplessness, his testiness, his occasional explosions, were all necessary steps, even welcome in their way, toward facing down his enemies.” This rawness though, “says nothing about the risks of exaggerating his enemies or becoming oversensitive to slights.” Thomas argues that this lack of self-awareness was Nixon’s fatal flaw.

As Thomas journeys through Nixon’s career the theme of “crisis” steadily mounts—the battle to win Eisenhower’s respect and the remarkably unaware “Checker’s Speech”, the loss of the presidential election to Kennedy, an “Eastern elitist” under dubious circumstances and torments of “dirty tricks” during the campaign, the perfidious nature of the North Vietnamese and the jealousies surrounding the fame of Kissinger, all tended to turn into events that Nixon considered betrayals. In truth, Nixon’s burning resentments, combined with pride, transformed his human relationships into battles. In the end he betrayed himself into the hands of lesser “yes men” men of dubious character, aides like Erlichman and Haldemann, Jeb Magruder, Dwight Chapin and, worst of all, shadowy “tricksters” like Gordon Liddy and the Plumbers, who escorted Nixon braying to the scaffold.

Nixon thought he knew “rock ‘em and sock ‘em” campaign tactics, some of which he’d suffered at the hands of Dick Tuck, a democratic trickster from the Kennedy campaign. Tuck was the one who once bribed a hired campaign band to play “Mack the Knife” at a Nixon appearance. At another, Tuck engaged a group of pregnant women to carry signs inscribed “Nixon’s the One!” Pretty funny, unless you’re a man under pressure who’s already taking Seconal to sleep, Dilantin to reduce stress, and regular doses of late-night scotch. What Nixon wanted to be was a “homme serieux” like Chareles de Gaulle; better yet, a public intellectual and man of action like Winston Churchill. Thomas writes, “Alone, at night with his yellow pad, he could imagine and yearn for a leader who was tough but compassionate, bold but wise, firm but gentle.” But in company Nixon often succumbed to anxiety. What he became was Walter Mitty in the bunker.

Thomas cites Nixon’s many achievements, some of which are both notable and forgotten amidst all the shameful profanity, anti-Semitism, racism, and criminal plans of the “Watergate Tapes”. Nixon was responsible for the Clean Air Act, the Water Pollution Act, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration Act, the Rail Passenger Act that created AmTrak, the vote for eighteen year olds, an office of consumer affairs in the White House, and even the Environmental Protection Act. On May 13, 1974, Nixon proposed to Congress a comprehensive program of national health care that, with its mandates, was not significantly different from what Barack Obama finally pushed through Congress four decades later.

This strange man, elected in a landslide by the American people, fell as dramatically from power as does a tragic hero in Aeschylus. There is a difference though. In the words of Thomas, “Aeschylus wrote that from suffering comes wisdom; Nixon’s tragedy was that he did not gain wisdom…” Perhaps if he and Kissinger hadn’t been such heedless murderers and liars, we’d be obliged to feel pity.