Sante, Luc. The Other Paris, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2015 (306pp. $28)

It is of no little interest that Paris contains some 3,195 streets, 330 passages (encompassing both arcades and alleys), 314 avenues, 2923 impasses, 189 villas (enclosed mansions, or house groupings like a mews), 142 cites (sometimes developed, sometimes a slum), 139 squares, 108 boulevards, 64 courts, 52 quays, 30 bridges, 27 ports, 22 galeries (arcades), 13 allees, 7 hameaux (quite literally, “hamlets”), 7 lanes, 7 paths, 5 ways, 5 peristyles, 5 roundabouts, 3 courses, three sentes (a kind of “path” or “way”) and…1 chemin de ronde, this latter being a raised walkway behind the battlement of a castle. In the mid-nineteenth century it puzzled and delighted one chronicler of the city that certain squares or intersections, through “mysterious forces”, always seemed devoted to a “single specialty”, an instinct that impelled the same classes or professions towards the same places. Thieves, pickpockets, beggars, street walkers, and street performers still inhabit the same haunts they did in the Middle Ages, in this case the Rue Pierre-Lescot, somewhere in the tangle of streets east of the Louvre, though sadly the tangle was nearly erased the infamous Baron Hausmann’s “makeover of Paris” during mid-century at the behest of a flummoxed old clod named Napoleon III.

In Luc Sante’s marvelously perverse, beautifully written, and gorgeously illustrated (some photos are rare glimpses indeed of unthinkably cockeyed scenes) new book we discover the inner secrets of the Rue Saint-Denis (one of the city’s oldest streets), where, ten thousand years ago a wooly mammoth wandered down from what is now the Belleville heights to the lowland swamps and marshes around the River Seine (then a meandering stream) and met its end, the skeleton and a few rags of dried skin uncovered by workers digging the Metro in 1903. Interestingly, under Roman rule, the street was a cour de miracles, the name given in the Middle Ages to an encampment of beggars whores and thieves. Even though today Rue Saint-Denis is rather clean and neutral, there are still filles publiques on display at all hours on its side streets. And before the King moved his palace to Versailles (suburban flight), royals regularly proceeded from the basilica of St. Denis north of Paris to their residence in the Louvre, following roughly the same path as the wooly mammoth.

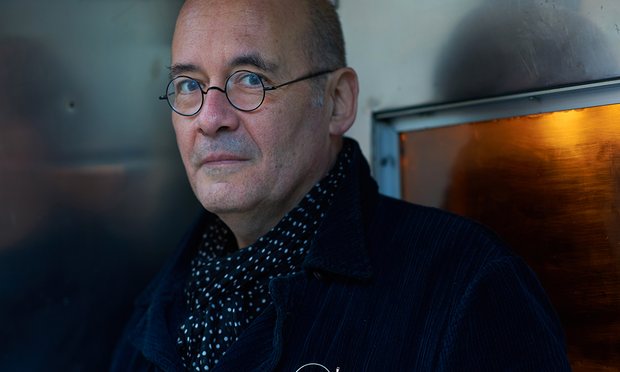

Sante, born in Belgium and the author of gleaming gems like “Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York”, recipient of numerous writing awards and a former Guggenheim Fellow, is the ultimate urban flaneur, whose quarry is the intimate world of Paris, its dens, warrens, milieus, neighborhoods, banlieus and zones; his story is one of intimate observation, psychological geology and architectural archaeology, each related in an adroit and penetrating style that results in a book much more dense, exciting, inspiring and mystical than any mere “portrait of a city”.

Instead, Sante’s Paris is one of profuse human interaction before the coming of the pan-optic of modern bustle. City dwellers take note that before the 1920s there were no commuters in Paris. Everybody on the streets tended to live and work in their own neighborhoods and each parish had its eccentrics, indigents, clerics, savants, brawlers, widows, fixers, elders, hustlers and busybodies. Before Hausmann configured the center into broad avenues and demolished Medieval Paris, every single house tended to have a shop on the ground floor, a shopkeeper’s dwelling on the mezzanine, a bourgeois family upstairs from the mezzanine on the “noble floor”, and then on up (without stairs) a succession of poorer and poorer families. At the top was the artist or student, the poorest of the poor. The geography and topography of the city was both material and human—the walls of the city were successive; Philippe-August’s wall in the thirteenth century, the Farmers-General just before the Revolution; Adolphe Thiers in the 1840’s, and finally the Peripherique highway completed in 1973.

Everyone and everybody in Paris is in Sante’s fabulous book: Gangsters and their lairs, nightclubs, nightclub singers and crooners, poets like Baudelaire and flaneurs like Walter Benjamin, police detectives, and criminals like Pierre Loutrel (a.k.a. Pierrot le Fou), great torch singers like Frehel, movie stars and courtesans, as well as prostitutes and courtesans (divided into classes from insoumises, horizontals and amazons (this latter a particularly glorious invention) all the way to grand cocottes and the chilling “man eaters”, all further subdivided into registered, unregistered, high class and low. Breweries, pubs and cafés all appear, along with their social histories. Wine dives had their own special provenance—the tapis franc, for example, a cavern where all the customers could be assumed to be criminals. Cabarets, theaters, movie houses, prisons, public execution venues and bookstores all share space in Sante’s book, as do revolutionists, the insane, and poets like Gerard de Nerval, doomed to suicide. Even laundresses do not escape his notice: In the nineteenth century there were 94,000 of them, according to an 1880 count.

In all this, Sante has a larger point. He writes, “The game may not be over, but its rules have irrevocably changed. The small have been consumed by the big, the poor have been evicted by the rich, the drifters are behind glass in museums. Everything that was once directly lived has moved away into representation.” With its engaging illustrations and penetrating insights, Luc Sante’s “The Other Paris” is an investigation into the fate of urban society in an age of Democratic Totalitarianism. His grand book suggests that it will be a long time before things get real again.