Prochnik, George. The Impossible Exile: Stefan Zweig at the End of the World, Other Press, New York, 2014 (390pp.$27.95)

Relentlessly middlebrow pop-intellectual Stefan Zweig, in the 1920s and 1930s, was the world’s most widely read and broadly translated writer of biographies, novellas and short-stories. For whatever reason, his easily accessible histories of figures like Marie Antoinette, Mary Stuart, and French idol Henri Balzac, still fill European bookstore windows like candy cane on Christmas trees. Oddly enough, he was, during his lifetime, hardly known in North America, though after 1934, on the run from Nazis and anti-Semites, Zweig lectured widely in both north and South America.

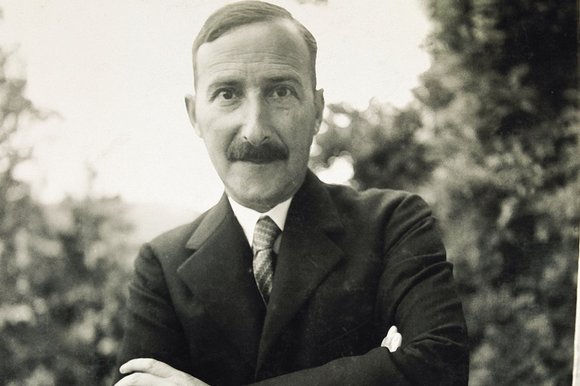

The story of Zweig’s wanderings (he was a restless and unhappy traveler) is deftly told in poet and essayist George Prochnik’s new book from Other Press, a work replete with excellent photographs and a fine index, and printed on lovely paper beautifully cut. Born to an ultra-wealthy Jewish textile manufacturing clan, Zweig became part of Vienna café society, living with his first wife part-time in a “castle” above Salzburg, but spending much of his working life traveling from one European city to another in a relentless and almost compulsive search for an inner peace which never appeared. Popular in South America, Zweig lectured in Brazil, and wrote a paean-style exposition of Brazil’s economy and government, which was then under the control of a fascist dictatorship, an effort which left Zweig in the uncomfortable position of mouthpiece for the Right Wing.

Prochnik focuses not on Zweig’s incurable prolixity, but on exile—the state of homelessness forced on many Jewish writers, artists and intellectuals after the ascension of Hitler and the Austrian Anschluss. Zweig was, at once, an affluent Austrian citizen, pan-European opponent of Zionism, impeccable host, chronic depressive, subtle womanizer (he dumped his dowdy wife for a younger, more pliable woman), dandy, fabulist, fawner after the powerful and champion of the powerless and, most importantly, coward in the face of old age. The evidence is clear that Zweig was invariably generous to his less fortunate exiles, lending money, marshaling housing, organizing benefits. To this day, Zweig’s work is popular in Europe in numerous cheap editions; to this day he is hardly known outside that continent, his work having fallen into obscurity even in Brazil, where he died, a suicide in 1941, having dragged his young wife into a suicide’s grave as well.

Two grand and imposing mysteries rise up in Prochnik’s book. Firstly, the very prevalence of anti-Semitism in Vienna (the Austrians were worse than the Germans, in fact) should have raised a red flag that things were about to turn dark. Instead, most Jews were anesthetized to the notion that anti-Jewish sentiment could become dangerous. Jews often described Austria as “an isolation cell in which screaming is allowed”. An epigram common in Vienna went: “Germans make lousy anti-Semites but terrific Nazis, while Austrians make terrific anti-Semites but lousy Nazis.” Sadly, it did not turn out to be true. They all made terrific Nazis. The second mystery is less earthly, but equally compelling. Zweig’s sexuality had an ambiguity at its heart, as did his endless wandering. He seemed to take no pleasure in either, but kept at both with the doggedness of a cat scratching fleas. Before Zweig arrived at one destination, he was already planning his departure.

The Impossible Exile, while not written in the most compelling style, nevertheless presents a readable profile of intellectual homelessness, a problem faced by other twentieth century artists and writers like Brecht, Joyce and Hemingway. As the twenty-first century progresses into increasing chaos, as borders break down, and as civil wars and religious conflicts produce increasing numbers of refugees— and as un-crossable political lines are drawn with barbed wire, drone surveillance, and “self-sorting”, many of us have come to know a kind of de facto exile, a metaphysical state as much as anything else. We come to share Zweig’s pain.