Harrison, Jim. The Great Leader, Grove Press, New York, 2011 (329pp.$24)

Harrison, Jim. The Great Leader, Grove Press, New York, 2011 (329pp.$24)

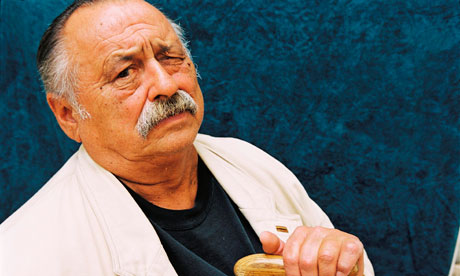

Though he’d forgive us saying it, and probably emit a chuckle, the great novelist Jim Harrison is a tad bit daffy. Maybe he always was, or maybe Americans ociety and culture, now gone entirely around the bend, is too easy a target for a superb artist like Harrison, who must ponder hopelessly the utter lunacy of a country that takes itself so seriously as the last bastion of liberty, leader of the free world, and chief dispenser of political twaddle masquerading as wisdom, not to mention being a country that thinks little of ruining its magnificent landscapes and destroying its wildlife.

So, it’s hard to know what was going through Harrison’s mind when he wrote “The Great Leader”, although it is a novel filled with Harrison’s trademark charisma, style, humor and lusty good will, along with endless paragraphs of superb observation.

For starters, let’s take Harrison seriously when he avers that “there is not truth, only stories.”

The Great Leader is a story about “Sunderson”, at age 65 a just-retired Michigan State Police detective who is also just-divorced from the great love of his life, an artist named Diane, who put up with as much of Sunderson’s drinking, late nights and existential trauma as she could.

After all, as Sunderson says, “law enforcement is a manhole cover on the human sewer.” What cop wouldn’t bring home both grief and whiskey after investigating a child murder, a rape, or a hit and run?

Sunderson, like Harrison himself, lives in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, a place just isolated enough to produce bushels of characters who, like the next-door neighbor and budding teenage nymph Mona, are attracted to Sunderson despite his many character flaws.

The plot goes something like this: Sunderson, with time on his hands, is asked by a local parent to investigate a cult leader named Dwight who is misleading and traducing local females who leave their homes and join his “commune”, where they’re sexually exploited and duped of their money.

In a nod to police procedural books, Harrison has Sunderson follow up leads, use computer systems, and engage in stakeouts.

Along the way, the reader is introduced to Sunderson’s ex-wife, his semi-estrange family which includes two sisters and their half-wit husbands, assorted and sundry bar maids, chambermaids, waitresses and femmes fatales, all of whom seem to find Sunderson interesting—lousy hygiene, alcoholism and all. He also eats a disturbing amount of fried red meat, liver, heart, sausage and other “heart stopping” foods. Sunderson sometimes pops gout pills.

Eventually Sunderson follows Dwight (who assumes aliases) to Tucson, thence to the Sqnd Hills of Nebraska, and back to Michigan. It won’t surprise Harrison’s followers to know that the book ends affirming the values of exuberant life, family (however it be defined), the natural world, and love.

The greatest Harrison novels are ultimately serious works that engage life on its most basic levels. “The Great Leader” is not such a novel, being mainly comic and satirical. The ultimate “solution” of the mystery lacks verisimilitude at best. It is, in fact, absurd.

But reading Harrison is always a pleasure, as nearly every page is a contagion of delightful insight and a burst of happy pleasure. Take this, for example:

It was near the summer solstice and he woke a little after 4am to the first faint light that far north. There was a dense profusion of birdsong on the liquid dawn air and he had the illusion that he could understand what the birds were talking about in their songs. The lyrics were of ordinary content about food, home, trees, water, watching out for ravens and hawks. It didn’t seem extraordinary and the ability to understand the birds lasted right up until he stirred the coals and made his coffee.

Harrison, the author of more than 30 books of fiction, poetry, essay and memoir, is perhaps our greatest American writer if judged by the fulsomeness of his vision of humanity (Balzacian), the lustiness of his prose (Millerian), the enormousness of his concern (Faulknerian) and the acuteness of his judgment (Didonian).

And while “The Great Leader” is not in the same league as his great novels—“Dalva”, “True North”, or “Returning to Earth”, it is a book that provides both enlightenment and joy. What more can we poor readers ask?