Harrison, Jim. The Big Seven. Grove Press, New York, 2015 (341pp. $26)

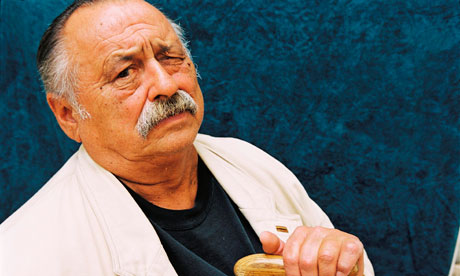

Jim Harrison’s formidable accomplishments include writing half a dozen of the best American novels of the past forty years (Dalva, The Road Home, True North, Farmer etc.), some poetry to break the heart (The Shape of the Journey: New and Collected Poems, Songs of Unreason, etc.), and a few unforgettable novellas like Legends of the Fall. This work, the product of a life-time of idiosyncratic experience in the outdoors of northern Michigan where Harrison no doubt observes the round of existence from a unique natural perspective (along with his world travels, his devotion to food and wine, and his love for dogs and trout fishing), carries the load for a mind that is both restless and determined.

With the creation one-book-back of his new character Sunderson, the protagonist of this lurid comic novel called “The Big Seven”, Harrison revisits trials of a retired Michigan state police detective whose problems are legion. These include an ex-wife Diane for whom Sunderson still longs, an erstwhile adopted “daughter” named Mona about whom Sunderson has sinful thoughts, and a drinking and despondency problem that would put the hardiest rock star to shame. Sub-titled a “faux mystery”, “The Big Seven” takes up where Sunderson’s previous adventure “The Great Leader” left off—with Sunderson desperately trying to make a go of it in his Michigan cabin, hoping to reconstitute his family life with Diane, and generally tying his moral shoelaces in big, messy knots. Where “The Great Leader” focused its “faux-hood” on a cult leader in Montana, the focus of “The Big Seven’s” so-called mystery is a family of backwoods rubes, criminals, sexual deviants and drunkards called the Ames, who happen to live one or two sections over from Sunderson near a river stretch full of big trout.

Sadly for Harrison lovers, “The Big Seven” never fulfills any promise to bring us wisdom or insight, and the shenanigans of Sunderson seem cartoonish, as our bumbling hero buffoons his way around the world and the country, even as he meditates the Seven Deadly Sins, most of which he commits heartily. A series of murders takes as its victims some of the Ames clan and suspicion falls jointly on 19-year old Mona Ames and aspiring writer and demented toad Lemuel Ames. The Ames are a caricature of rural hickhood, ardently murderous, incestuous and wily. Harrison halts the “faux mystery” several times in mid-sentence, once sending Sunderson to Mexico for a long vacation full of booze and food. There are extended asides, distracting and feverish and unbelievable, too. When Mona runs off to New York and then Paris, Sunderson trails along, brews up an extortion plot to subvert the wiles of a rock-punker with whom Mona has fled, and manages to cop $50,000 from the mother of the rock-punker by threatening exposure in the tabloids. This nonsensical side-plot takes up a lot of space but serves as a mental enclosure whereby we can understand Sunderson, nearly broke, driving and flying and drinking and eating as if the sky were the limit. Unfortunately for Sunderson, he winds up with a broken back in a bar fight.

Go figure. After much to-ing and fro-ing, the novel meanders its way around the seven deadly sins as if looking for its cause de celebre where none exists. There are brawls galore, gunfights, bodies washing ashore and fantastical sexual gymnastics that can only be described as authorial wish fulfillment. Some are, in fact, frankly embarrassing, as only an old man’s fantasies can be when publicly expressed. Harrison’s trademark intelligence and insight appear occasionally, but with nothing like the artistic and personal integrity we’re used to from such a gifted writer. Here’s hoping that Sunderson finds quiet with his beloved Diane, and together they are written out of the script.