Second Look Books: Julip by Jim Harrison (Houghton Mifflin, $21.95) Originally published on July 10, 1994. Jim Harrison died last year. His passing is a great loss for American letters.

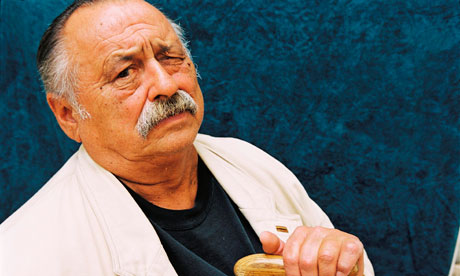

Jim Harrison is one of our very best American writers. He is the author of six novels, including “Wolf”, “Farmer,” “Warlock” and “Dalva,” the latest named being something of a doubly rare achievement, both a novel of spiritual power and a work of imagination about female life penned by a man. Harrison is also a poet of some note, a gourmand of extraordinarily epic tastes, a great curmudgeon and, if we are to believe his image, a bit of a cad, this last to be taken in its best sense.

An ostensible member of the Michigan-Montana-Key West gang that includes Richard Ford and Tom McGuane, Harrison is a muscular writer in the sense that he prefers the straightforward approach, as when, in a story in the present volume titled “The Seven-Ounce Man,” a character called Brown Dog discovers, or better, reflects, upon a slice of his most recent past: “In the cabin it occurred to him that he had done so much worrying he had been neglecting his drinking.”

As much as anything, Harrison is a writer of the truth about American life as it is today, life full of pusillanimous harms, that pukesome social cud (mixing many metaphors) constantly chewed and never swallowed. He hates, in short, political correctness, campus life, suits and ties. He loves nature, food, life and experience. Relationships don’t much concern him as the subjects of art and his motto may as well be: Take care of yourself and the rest will take care of itself. He is neither a selfish man nor a mannish self. He simply knows how to go from A to B without the aid of psychodrama.

“Julip” is as collection of three longish novellas. Each in its own way is a charming, deliciously complicated and complex work of fiction, standing whole and nearly perfect. Harrison is almost alone among American writers in his love for, and devotion to, this form, a form that requires the ethereal hand of the poet and the earnest devotion of the novelist.

‘Julip’

Julip herself, heroine of the first story, is a dog trainer and self-appointed savior of her brother who is jailed in Key West on a charge of attempted murder, the victims being three of Julip’s worthless lovers. Julip-Harrison (for she is nothing if not a descendent of her author-father) is a direct kind of gal, who goes to bed with a half-baked southern Georgia lawyer in lieu of a fee, and who describes old boyfriend Jim Crabb (another dog trainer) in these poignant terms—“She had known him since childhood, and if anything the sense of general dreariness he filled her with had increased. He was, simply enough, the lamest head she had ever met.”

Traveling from Wisconsin, where her father, a deeply devout alcoholic, has killed himself, Julip undertakes an odyssey of redemption on behalf of the crazy son in her family. Her task is to convince the three victims to forgive the criminal charges so that brother Bobby can spend a few months in the nuthouse rather than a few years in jail. The lovers are symbols. Charles is a photographer, Arthur a painter and Ted a writer. If a book reviewer were tempted to be serious, he would argue that the Julip-lover connection is an encapsulation of the struggle to free art from its commercial, and thus, neurotic, source.

Of Charles, Arthur and Ted, Harrison writers: “In previous times more slack would have been cut for this threesome, but this is an age when not much slack is cut for anyone.” Harrison is never more imaginative than when he is writing (as a man)about a woman (his creation) thinking about what a man (his character) thought about women. “And it was the rock-bottom puzzlement of his life and time: there is an ideal woman who will return to you the kind of sexual life you could have had at 19 but didn’t.” This is a statement so nakedly true it hurts me to think about. “Julip” is a funny and moving ode to redemption and the return to innocence, fully sexy non-violence and non-violent sexiness, dense with revealed truths.

‘The Seven-Ounce Man’

In the “Seven-Ounce Man,” Harrison returns to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, which is home turf to a continuing character named Brown Dog, B.D. for short. Forgive me for saying this, but stories set in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, including as they do the “Big Two-Hearted River”, mosquito clouds, and cold starry nights, cause a certain literary lump in my throat. In this case, B.D. who has fallen under the watchful eye of the FBI and the Michigan State Police for interfering with a university anthropological dog (short for excavating an Indian burial mound), is intent on looking up an old love, Rose, an Ojibway trailer-woman. Unfortunately for B.D., Rose is singularly interested in whisky and bad wine, amatory only late at night when the TV flickers whitely and the trailer trembles in the wind. But B.D. has always had a simply philosophy, one given him by his grandfather. “As Grandpa used to say, it is not in the nature of people to understand each other, “Just get to work on time, that was the main thing.” It was also Grandpa who warned B.D. against fighting the battles of others. But, in this case, that is what B.D. is letting himself in for when he considers once again trying to stop the excavation.

Brown Dog must live very deep in the soul of his creator, for how else could B.D. express such heartfelt Harrison emotions about women—“women still beat the hell out of men to be around. You weren’t always cutting and bruising yourself on their edges.” Speaking as a man, I announce this as an eternal truth. Suffice it to say that “The Seven-Ounce Man” is an adventure story full of verifiable lunatics. It is fiction with the odor of a pine-paneled tavern and is laugh-out-loud hilarious.

‘The Beige Dolorosa’

The last of Harrison’s novellas, “The Beige Dolorosa” is, if you will forgive the allusion, a horse of a different color. Its central character, Phillip Caulkins, is an English professor very late in midlife, who has lost his job due to an unforgivable lapse into political un-correctness having to do with some misstatements in class, and the perception of sexual harassment he must have exuded somewhere on campus.

None of it is true of course, and none of it ought to destroy a good man’s career, but destroy it does, nevertheless, which is a comment upon the current state of campus life and our own incredible dependency on syntax to the exclusion of common sense. Caulkins, without career, retires to southern Arizona to get his bearings and, worried-over by his married daughter, comes into contact with nature for the first time. And it is the natural world—the thriving green grasslands just north of Mexico, the rolling hills and long-vistaed mountains, and the abundant bird life above all—that revive Caulkins and return to him a humanity he has lost.

The first thing that nature does to Caulkins is envelop him in childhood memory. “On seeing the winsome girl I had a ghastly shudder pass over my body, remembering in an instant the girl I saw at the far end of my paper route, whose name was Miriam, and whom I loved with the desperation one is capable of only once in a lifetime.” Caulkins is recovering the physical body, his first possession.

In his retirement Caulkins conceives of a project to write a new guidebook to birds, a guidebook which would rename each species. For instance, the “brown thrasher” would become the beige dolorosa, a name worth of the beauty of its holder. All at once Caulkins realizes the deeply spiritual consequences of the natural world. This realization, or regeneration, strips Caulkins to the bone, which is one way of saying that it releases his inner being. “I must add that nature has erased my occasional urge toward suicide…For the time being I am too much a neophyte to take part in defending it against the inroads of human greed. There is also the idea that I’m a newborn babe with a soft spot on the top of my head. My natural enemies would still crush me.”

In historic terms, the death of nature is near. In a world of screens and fiber optic cable, of information networks and superhighways, in an economic system driven by consumption, mass replication, and instant reproduction, there is precious little room for contemplation, for quietude and simple wonder. In his own way, and with great art and dignity, Harrison asks each of us to convert himself, to re-spiritualize himself, to constitute a chorus of one. It is, as always, a lonely plea that few will hear and fewer will heed. But we owe Jim Harrison a debit of gratitude for making it.