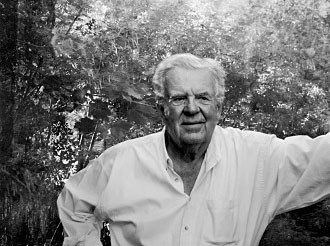

Second Look Books: Hole in the Sky by William Kittrege (Alfred A. Knopf, $20) Review first published Sunday, August 30, 1992.

Second Look Books: Hole in the Sky by William Kittrege (Alfred A. Knopf, $20) Review first published Sunday, August 30, 1992.

It seems impossible, but there is a place in America that is so empty, so terrifyingly beautiful, that one, on seeing it for the first time, would almost imagine that the country had hardly been touched by civilization at all. Bordered on the north by the John Day River, on the south by the lunar-lava landscape of Pyramid Lake and Mount Shasta, on the west by the great Cascade Range, and finally, on the east by the mysterious Owyhee mountains, this land, southeastern Oregon, is truly an American treasure. But untouched by civilization it is not.

Into this country, in July 1911, rode William Kittredge, grandfather and namesake of William Kittredge the writer, a man who owned cattle in California, and who was looking for a place to feed them and fatten them for market, which is the same thing as saying that Bill Kittredge was looking for a competitive edge. What he found that summer was the Warner Valley, near what is now Lakeview, Oregon. The native peoples, Modoc and Paiutes, had long before been run off, enslaved, murdered, marched and exterminated, and what was left was a windswept basin and range country studded by shallow seasonal lakes filled with Tule and cattail, long green runs of grassy hills, spring creeks in abundance, and millions of water birds, both spring and fall, coming and going to Canada. Yellow monarch butterflies floated in the breezes, and there was a 6-foot thick layer of rich peat for topsoil laid down over the millennia.

Bill Kittrege looked at all this country—the silence, and what he saw was an empire, country waiting to be worked up into a healthy profit.

“Hole in the Sky” is the story of what this profit meant to a family, and to a territory, a kind of cautionary tale in which love is subtracted from the earth and its inhabitants, and the sum is totaled. William Kittredge, the writer, grew up in the Warner Valley, with stopovers at Klamath Falls and Palo Alto for education. He watched the irrigation ditches being built, the lake beds and tule fields plowed; he watched the cows move in and chew out all the grass. He learned the rules of ranching—handle your horse and never hire someone you drink with. Kittredge’s own father and mother became estranged, there were jealousies over money and influence, the ranch and family fell apart at about the same time the land gave out and went to leached salt because all the water had been pumped out. This is the caution—this is what happens when love is subtracted from the land and its inhabitants.“Hole in the Sky” is lovely and terrifying, a kind of ultimate search for things as they should be, for childhood and its immediacy of feeling, and for what went wrong. Kittredge writes with tremendous feeling about the ranching life, the loneliness of the cowboys, the vastness of youth.

“I want to see the Lombardy poplars and apple trees and posts supporting the woven-wire fence around the house where I lived in that boyhood, I want to see if they are glowing in the luminous world. I want things to be radiant and permeable. I want to be welcome inside these memories if nowhere else, and think I was welcome as a child.”

Kittredge the writer drifted away from the Warner Valley and into the Air Force, and into a marriage that seemed to have no reason to exist. He drank too much, and was unfaithful, and fell headlong into depression. Parted from the land, subtracted from his family, he was alone.

As a memoir, “Hole in the Sky” is worth to stand beside Norman Maclean’s “A River Runs Through It,” though Kittredge falls short of Maclean’s unique fictive ability. But Kittredge excels at recreation, and has an almost haunting ability to lift the veil on a scene—a dusty barroom, for example—and reveal the marrow of its hypnotic sadness. If there is a fault in the book, it is that the concluding section, devoted almost entirely to environmental concerns, is structurally out of square with the tone of the rest of the book. Sadly, too, Kittredge says little of his own children, and seems unable to heed his own cautionary words in this regard.

Most of us, Kittredge says, are eager to live in connection with a specific run of territory and its seasons, in some intimacy with the animals that happen to inhabit that country creature to creature.

How true. And how many of us are subtracted from this need.