Hackman, William. Out of Sight: The Los Angeles Art Scene of the Sixties, Other Press, New York, 2015 (308pp.$27.95)

A forty thousand year continuum separates the Cro-Magnon shaman painting ochre-and-earth pigment aurochs on the walls of Lascaux cave from the billionaire collector purchasing a mediocre hundred million dollar Picasso at an auction in London conducted by Sotheby’s. For the shaman, auroch images represented, most likely, a deeply held sense of magical superstition exorcised by individual imagination, both in service to a hunting ritual geared to the worship of natural and invisible spiritual forces. And while Picasso probably shared some important aspects of sensibility with the shaman, the billionaire collector is almost certainly a Veblenesque show-off. A book like William Hackman’s “Out of Sight: The Los Angeles Art Scene of the Sixties”, with its entertaining and insightful investigation of “art sources and methods”, its engaging discussion of personalities and movements, and its perceptive analysis of commerce and promotion, provides the reader with what can only be called a “natural history” of modern art on the West Coast.

Like Paris and New York, Los Angeles at the beginning of the twentieth century was a large city. Unlike either Paris or New York, Los Angeles was, in the words of urban planner Kevin Lynch, “hard to conceptualize as a whole; it was, for all intents and purposes, illegible.” At the turn of the century, Los Angeles, a collection of dusty provincial towns full of Midwestern pilgrims, was a sprawl of de-centered un-geographical geography, a semiotic riot of disparate parts with no visible architectural coherence and no public awareness beyond boosterism. No unique public buildings graced a central core; its homes were copies of the Victorians of New England. A provincial mob of rich nabobs controlled the politics, business, and police and of the place, and its art patrons were society ladies in Pasadena for whom art consisted of lacy portraits and frontier landscapes. And while Los Angeles had a museum—the Los Angeles County Museum, the museum showcased only low brow western art and dinosaur bones.

William Hackman, a former managing editor at the J. Paul Getty Trust and longtime art, music and theater critic, shows how Los Angeles got its artistic swagger beginning around 1962, a year Hackman calls the “annus mirabilis” for LA art. It is true that LA had the semblance of an art scene in the 1920s and 1930s, when the Bauhaus aesthetic paid a visit as various European emigrants came calling on the run from Nazis. But it took a while for LA’s essence to form and sink far enough into the sensibilities of individual artists that a true “art scene” could emerge by 1952, when a young man named Walter Hopps plunged headlong into the “murky depths of modern art”. Hopps, it turns out, became an art entrepreneur, co-founder of the famous Ferus Gallery, and sponsor of Ed Keinholz’s scandalous assemblage installations. Assemblage became the way that LA finally rejected New York’s dominant abstract expressionism and began to stand on its own two feet.

Anyone who’s been in LA enough can understand the city’s “illegibility” as the core source of its semiotic power. The wide boulevards and impressive historical heft of Paris and the massive drive and awe-inspiring might of New York point towards art scenes with weighty consequences. LA’s landscape blazes not with power, but with a mysterious yellow light, a territory consequent in blue, gold and lavender. Not for nothing did LA draw, during the 20s and 30s, a gaggle of spiritualists, yoga enthusiasts, drug advocates and theosophists. It was both groovy and kookie, the perfect kitsch antidote to the profundities of New York’s abstract expressionism.

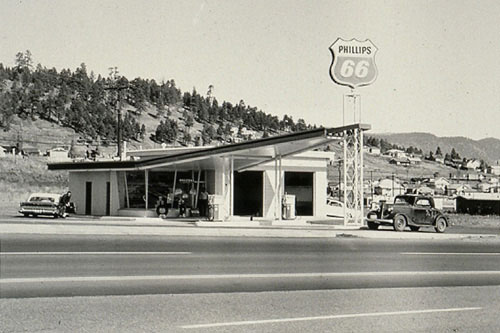

LA seemed the right place to first show a young advertising executive named Andy Warhol and his delightfully whimsical soup cans. It seemed the right place for Ed Ruscha to paint his works dominated by a repeating loop of signifiers that seemed to lead in a circle back to a starting place in the Western landscape that blazed with the un-nameable. In Hartman’s words, the LA art scene hovered somewhere “in a place situated, however precariously, between suburbia and the sublime.” This was the place where service stations, shopping malls, palm trees, blue oceans and barren hills became what skyscrapers were to New York, what ballerinas were to Paris. When, in 1965, the city built the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, something was definitely up in La-La Land.

LA artists didn’t wear smocks and hang around in cafes. Light and Art sculptor Robert Irwin came from hot-rod culture. Painter Billy Al Bengston rode and raced motorcycles, while sculptor Ken Price surfed. Actually, most of them surfed. Ed Keinholz, the self-described “constructionist” had no formal art training. Many were interested in technology, plastics and, like Wallace Berman, Zen. The LA scene also included some true Beatniks, like assemblage artist George Herms and collector Dennis Hopper. Most openings featured a smattering of movie stars like collector Vincent Price (a true connoisseur), Russ Tamblyn, and Rolling Stone Brian Jones. LA produced art that New York couldn’t: mirrored plastic or Plexiglas boxes throbbing with inner light, rectangular landscapes full of translucent or shimmering emptiness, a Texaco sign pointing towards transcendence. Even the smog connoted mystery.

LA’s art scene demonstrated that “the deepest kinship between the Light and Space movement and contemporaneous trends within LA was with such artists as (Vijia) Clemins, (Joe) Goode, and (Ed) Ruscha and the ways they responded to the distinctive light and wide-open spaces of Southern California.” There is, really, no place in the world like LA and its art scene, so influenced by suburbia’s tacky symbolism, dry desert air suffused with brilliant yellow light, a vast freeway system as rigorous as a prison, and its haunting canyons and late summer wildfires. As Hackman concludes about LA’s 60’s art scene, “It won’t happen again. You had a big city that was largely disconnected from the global cultural world, and a critical mass of things came together at exactly the right moment.”

Hackman’s fine book “Out of Sight” documents a cultural movement of great American moment. If you wish, take a look at the iconic album cover of the Beatles’ classic “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” There, directly above John Lennon, two rows up, one finds the transformational Beat Generation figure Wallace Berman, who was god-father to the LA scene. He’s right next to Tony Curtis. Not pictured is the Lascaux shaman.