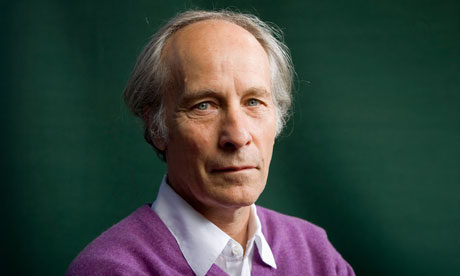

Ford, Richard. Let Me Be Frank With You, Ecco (Harper Collins), New York, 2014 (238pp.$27.99)

The loathsome character Frank Bascombe continues to tunnel away at writer Richard Ford’s time and talent, both of them, writer and main character, now nearly hollow, each nearly filled to ooze-point with snide metaphysical certainty, hateful disdain for common virtue, and a smirking buddy-buddy haughtiness not unfamiliar to male Middle School culture. Ford continues to write beautiful prose—maybe too beautiful by half, a prose haunted by narcissistic prancing. Bascombe, his face always in the mirror, ages, but sheds wisdom, honor, kindness, decency, fellow-feeling and hope, as if all these acknowledged ideals were just body armor and not, as most of us think, warm skin that grows between us and the Monstrous Emptiness.

In his original incarnation (“The Sportswriter”, 1986), Bascombe was a man in a bad marriage wounded by the death of his son. He became withdrawn, guarded, and emotionally detached. In the bloated “Independence Day” (1995) and the hyper-bloated “Lay of the Land” (2006), Ford moved Bascombe to New Jersey, where he became a realtor in the suburbs and exurbs where the hollowing out—environmental, existential, emotional, sexual and personal, commenced in earnest. The endless malls, freeways, bridges, residential tracts, and commercial zones of New Jersey’s shore, melded with Bascombe’s behavior to create an unflattering drama of America entering a truly materialist phase, coupled with civic and physical decline pictured by Ford as a mordant satire, fleece-lined with a brilliant writer’s spiraling syntax, letter-perfect vocabulary, and subtle but empty intelligence.

“Let Me Be Frank With You”—has there ever been a worse (almost self-consciously bad?) title, links four short stories that take place during the Christmas season after Hurricane Sandy has laid waste to large portions of Bascombe’s hunting grounds. Luckily for Frank, he sold his shore house to a guy named Arnie and his new house remains unscathed, his pot of equity still in tact. It goes like this: Story One—Arnie, in despair, calls on Frank for advice about his destroyed property; Story Two—a black woman (a “vestigial Negro, in Frank’s lingo) visits Frank at home with a terrible family story to tell; Story Three—Frank takes an orthopedic pillow to his ex-wife Ann, now suffering from the onset of Alzheimer’s; Story Four—an old “friend” Eddie, now on his deathbed, calls for a visit from Frank, who reluctantly goes, only to be told a confession.

In each case, something is asked of Frank. Arnie wants hope and fellow feeling; Ms. Pines (the vestigial Negro) wants only a little time to contemplate her past; Ann hopes to talk about their shared children, but knows Frank too well to expect much; Eddie wants to get something off his chest before dying. Frank makes not a single concession to any of these people, regarding them as either annoyances or specimens. Contemplating his children and their lives occupies Frank a little, but their status and Being he regards as purely a social function, nothing more. As a “professional liberal”, Frank reads to the blind and welcomes veterans home from the Wars at the airport, but even these acts he looks on with cool dispassion. (“This fall, I’ve been reading Naipaul’s “The Enigma of Arrival”, thirty minutes is all they can stand…From all I know about the blind from the letters they send me, they’re pissed off about the same things he’s pissed off about—the wrong people getting everything, fools too-long suffered, the wrong ship coming into the wrong port.”). Ann’s staged-care facility looks like “the home décor department at Nordstrom”. Frank’s compassion is easily summed up in his reaction to Arnie’s need: “Like most conversations between consenting adults, nothing crucial’s been exchanged. Arnie just needed someone to show his mangled house to. And there’s no reason that someone shouldn’t be me. It’s a not-unheard-of human impulse.”

The writer Ford tells us that the character Bascombe is exhibiting his “Default-Self”, the assemblage or impersonation of a human being, allowing the character not to seem cynical. More likely is that Richard Ford has become the Default-Writer, talking to his readers in the guise of a man who is supposed to be a retired sportswriter, sexless realtor, and faux-friend, but who, nevertheless, makes knowing asides about “go-to-Roethke” modes of conversation, or who spouts references to Auden in a casual and knowing manner, and to Obama “getting his little black booty spanked by Romney about fiscal stewardship”. Here, in the poetry references and clean-lined cleverness, Ford upstages his main character in a way that a writer like Balzac or Bellow never did.

Some of Ford’s opinions are so vile as to be unforgivable. “Where I was standing in my pajamas, staring out the front window as the Elizabethtown Water meter-reader strode up to the front walk to check on our consumption, my mind fled back to the face of the ultra-sensual Mary (of Peter, Paul and Mary…)—cruel-mouthed, earthy, blond hair slashing, her alto-voiced promise of no-nonsense coitus you’d renounce all dignity for, while knowing full well you couldn’t make the grade. A far cry from how she ended life years on—mu-muu’d and unrecognizable. Which one of the other two was the weenie waver?”

Aside from the unforgivable falseness of this picture of a beautiful, talented, giving, loving, full-of-hope and politically committed woman, as well as the pointless sexual innuendo, there is the gaunt and purposeless nature of these dual insults, delivered sotto voce. I guess it doesn’t matter to Ford or Bascombe that Mary Travers was suffering, later in life, from terminal leukemia.

Sexless, joyless and emotionally cruel, Frank Bascombe deserves place of pride in one of the Circles of Hell. In his own words: “My mass has simply been deemed deficient…Character to me, is one more lie of history and the dramatic arts. In my view we have only what we did yesterday, what we do today, and what we might still do. But nothing else—nothing hard and kernel-like. I’ve never seen evidence of anything resembling it. In fact I’ve seen the opposite: life as teeming and befuddling, followed by the end.”

So much for Huck on the Mississippi; so much for Nick Adams on the Big Two-Hearted River; so much for Walt Whitman and Philip Roth and the existential courage of Albert Camus. So much for what we’ve learned from the Greeks and Romans, the Christian martyrs; much less what we learned from the guys on Omaha Beach at D-Day. What Ford serves up is Frank Bascombe, with his spoiled Swiss cheese soul.