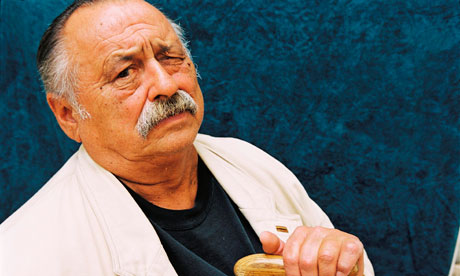

On Saturday, March 26 Jim Harrison died at his cabin near Patagonia, Arizona. He’d been ill and his wife of many years had died the previous October. His loss is grievous one. I’ll miss his books and I’ll miss his wisdom in my life. Here’s my review of his last book of prose. He’s got a new book of poetry out too–“Dead Man’s Float” from Copper Canyon. So long Jim, take care and have a glass of Beaujolais for me.

Harrison, Jim. The Ancient Minstrel, Grove Press (Grove Atlantic), New York, 2016

(255pp. $25)

Midway through “The Ancient Minstrel”, the first in a trio of short novellas (or long stories), Jim Harrison pauses to reflect on the writing art and its relation to immortality. “…he knew very well that writers in weak moments have always historically looked for philosophical underpinnings for their work. There were none that were not nearly laughable. Such campaigns were almost always led by the weakest writer in a group who had the most to gain, a fragile snippet of immortality as part of a ‘movement’.” Harrison, one of American’s great writers—whose work could be said to have absolutely no philosophical underpinning, briefly praises the “Beats” who, he argues, “had quite a bit of substance” in contrast to academic poets, who collectively resemble a cornfield under drought conditions. Harrison, an outsider, a man who rejects city life with its struggles and dissolutions, surfs the buzzing confusion of experience and reports on it with a voice that outlasts the noise. “Writing like nature was full of unfairness,” he concludes. “Hail killed baby warblers in their nest. Wars were obviously part of nature and killed millions. The mortality of songbirds hitting windows drove him crazy. You had a lovely life ahead of you and then you struck a window and it was over.” Harrison knows what he’s talking about: His father and nineteen-year-old sister were killed in an automobile accident; Harrison lost an eye to a childhood accident.

“The Ancient Minstrel” is Harrison’s eighth collection of novellas—a considerable body of work; however, his oeuvre also consists of eleven novels, thirteen volumes of poetry, a long memoir and two books of essays. He’s spent his life, he says, walking the woods, plains, gullies, and mountains, and considers himself mostly lost and vulnerable in the world, a feeling he describes as the “best state of mind for a writer whether in the woods or the studio. Your mind feels a rush of images and ideas. You have acquired humility by accident.” In the title story of this enormously engaging book, Harrison sloshes around in the detritus of his own life. What emerges in the end is a meta-memoir with none of the fireworks of experimentalism. His has been an autochthonous life, the life of a minstrel, one of those wandering poets whose songs explore the stories and narratives of popular imagination. As readers, we’re obliged to understand that most stories are lies that tell the truth. Harrison himself has been through a lot. He’s struggled in the shadows of poverty, drugged himself silly in the Hollywood game, fished for trout in Michigan, and drunk too much red wine and eaten too much meat and loved the French countryside. “It’s our dreams and visions that separate us. You don’t want to be writing unless you’re giving your life to it. You should make a practice of avoiding all affiliations that might distract you. After fifty-five years of marriage it might occur to you it was the best idea of a lifetime. The sanity of a good marriage will enable you to get your work done.” On the other hand, the title story is also about raising a litter of pigs.

Perhaps the best piece in the book is called “Eggs” and continues in the mien of an earlier Harrison story called “Woman Lit by Fireflies” or a novel called “Dalva.” In this appealing and emotionally wrenching tale, a young girl named Catherine grows up in an alcoholic household riven by tension and disappointment. Later, living on a farm outside a small Montana town (Livingston) with her grandparents, she grows attached to raising chickens. As an adult, Catherine travels and lives a solitary life on the farm, wanting a child but not wanting to be married. Most happy on the farm and in the fields, she nevertheless is forced to deal with her aging, alcoholic father, a rich insensitive step-father, and a mother with reconciliation on her mind. She finally has her baby by seducing a World War II amputee who later commits suicide.

In the shortest story, Harrison conjures and disposes of Detective Sunderson, a recurring character from books like “The Great Leader” and “The Big Seven”, a hard-drinking, sexually undiscriminating and self-regarding semi-hooligan whose adventures require a lot of readerly suspension of disbelief. This particular story, and the Sunderson saga in general, aren’t in a league with Harrison’s other continuing characters like “Brown Dog”.

Undoubtedly Harrison identifies with medieval French minstrels “who became an ultimate symbol of freedom in an authoritarian society.” He is, he tells us, still plagued by a childhood dream of minstrels in heavy blackface makeup, from which he wakes drenched in sweat. In this regard, his achingly beautiful character Catherine concludes, “She saw life as more of a constant whirl in which people often behaved badly. What was the point of forgiving the early whirls? The past lives on in all of us. No matter how wronged we were the offenses were only the beaten-up junk of memory, pawed over until they were without color.” We are, if Harrison is right, all the characters in a story about minstrels. In the background is a stage and on the stage are players whose message is one of mortality, loss, revision, joy, staggering regret, affirmation and pity. Savoring the whirl is the work of a writer like Jim Harrison. And if he’s right, we’ll find humility by accident.