Coleman, Jon T. Here Lies Hugh Glass: A Mountain Man, A Bear, and the Rise of the American Nation, Hill and Wang, New York, 2011 (252pp.$28)

In 1823 Hugh Glass, journeyman hunter and trapper, signed up to serve the American Fur Company as a hunter on its spring expedition up the Missouri River to the Arikira country and beyond, where a hundred men young and old (Glass was old) would find beaver pelts for the New York and European hat trade. Led by William Ashley and Andrew Henry, both members of the St. Louis political and business aristocracy, the American Fur Company was a purely capitalist enterprise and the hundred men young and old were purely the piece-paid proletarians.

Glass was lucky to be a hunter. Others that spring had worse jobs, dragging the flat-bottomed trade boats upriver against a strong spring current, or cooking, or worse, fighting the Arikiras and Blackfeet, who, rightly, resented the upstart Americans raider their beaver streams.

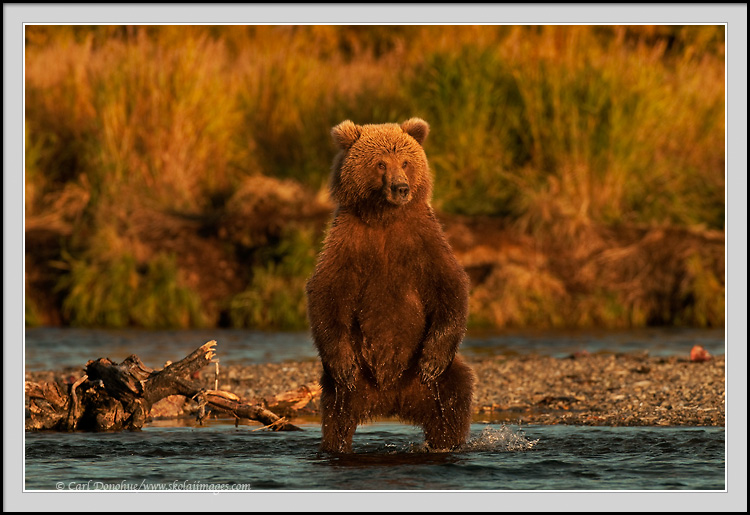

Two months later Glass found himself wading through willows in the company of two other hunters who would become legendary—Jim Bridger and Tom Fitzpatrick. Suddenly, Glass found his head inside the mouth of a big blond Griz (hunters called the “white bears), then thrown like a rag doll, ending up on the ground with a gash down his entire body, head to ankle. With Glass near death, Ashley instructed Fitzpatrick and Bridger to remain with Glass until he died. Instead, Glass’s two companions left him after a day, thinking he was sure to pass. Alone, he crawled 325 miles to Fort Atkinson and survived, only to be killed by Arikira 10 years later along the Yellowstone.

Coleman, an associate professor of history at Notre Dame, has written a book about Hugh Glass in which Hugh Glass hardly appears for the simple reason that the “real” Hugh Glass is known to history only through a few scattered tales along the frontier and one letter of condolence he wrote to the parents of a hunter slain by Indians. What looms large, however, is the conflated, overblown legend of Hugh Glass as a man who endured a bear attack, fought Indians, overcame harsh environmental conditions, cold winters, bitter thunderstorms, and, at the end, became the message-bearer of American exceptionalism and Symbol of the Nation. Like Davy Crockett, Mike Fink, and Daniel Boone, Glass made the American case against the native peoples, free blacks, slaves, Mexicans and British, who all stood in the way of an American Empire, sea to shining sea.

Coleman is a deconstructor of our National Frontier Myth and draws into his sometimes quixotic, sometimes colloquial, and sometimes compelling argument, a close examination of newspapers, regional literary journals, and even the works of writers like Herman Melville. Glass was a Nobody made into a Hero by hack writers like James Hall and Timothy Flint (who simply made up Hugh Glass out of whole cloth) and foreign adventurers like George Ruxton whose published diaries interpreted the American West through the prism of an already inflated and vividly panoramic European imagination of the frontier.

Glass’s journey form anonymity to minor celebrity, writes Coleman, “opens new sight lines on the interplay of culture, labor, nationalism and nature in the American conquest of the West.” Glass, as late as 1971, was being portrayed in the movies by none other than English actor Richard Harris (“Man in the Wilderness”).

“Here Lies Hugh Glass” is hampered by the author’s recondite style and his self-inflated sense of humor. Read carefully, however, it shines a pure light on the actual conditions of the working man in the American West, on the fundamental relation between men, animals, and Native Americans, and on the many rascals and scamps, not to mention confidence men and counterfeiters, who are the real source of our greatest national myths.