Millard, Candice. Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President, Doubleday, New York, 2011 (339pp.$28.95)

In 1829 Abram and Eliza Garfield bought a hundred acres of heavily forested wilderness (at $2/acre) 16 miles from the tiny Ohio village of Cleveland, an isolated two miles from the nearest rutted wagon road. Farming was far from easy for the couple, and a few years later when a massive wildfire ignited in the forest, Abram fought it single-handedly by digging ditches and hacking brush fire breaks. He won the battle against the fire, but lost his life that summer to fever and exhaustion, leaving his wife with four mouths to feed, among them James, who would grow up to be America’s 20th president.

Candice Millard’s compellingly told and beautifully researched account of the wounding, suffering and death of James Garfield in “Destiny of the Republic” is first rate popular history, free from the hedging language problematic of so much of the genre (he might have said, must have felt, surely thought), underpinned instead by a complex weave of newspaper accounts, personal diaries (people of the time were compulsive diarists) and letters, along with comprehensive library research, research which even included interviews with Garfield’s surviving heirs. Millard, who lives in Kansas City, and whose previous book, “The River of Doubt” (which chronicles Teddy Roosevelt’s catastrophic descent of an Amazon tributary) was named a New York Times Notable Book, has written for many prominent national magazines, and is a former editor of the National Geographic. She is surely on her way to a national reputation.

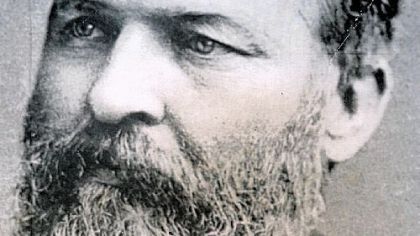

Like Lincoln’s stepmother, Garfield’s mother Eliza fought passionately for her son’s future, eventually sending him to a local technical college called Eclectic Institute. From there, Garfield went to Williams College in Massachusetts where he excelled in liberal arts. As a youth, Garfield had gone to work on the Erie Canal as a bargeman. A near drowning convinced him that college was where he belonged. At the astoundingly young age of 26, Garfield became president of the Eclectic Institute and one of its very finest intellectual leaders. By all accounts Garfield was a gentle and devoted father to his five children, a loving husband to his esteemed wife, Lucretia, a loyal friend to the many people who coveted his acquaintance, an honest man and sincere citizen. During the Civil War he served with distinction as a general, leading an Ohio regiment in several major battles. He became a congressman and later a senator from Ohio in 1880—and then a reluctant and entirely unexpected compromise Republican candidate for president in the thoroughly rotten year of 1880. Garfield was a reasonable man who believed in science and art, and who practiced Christianity in his everyday life, who espoused the rights of freedmen, and fought hard to reform the spoils system.

Garfield’s murderer, Charles Guiteau, on the other hand, was a schizophrenic with paranoid fantasies of grandeur and persecution. He fancied himself a servant of a wrathful God. He told himself that he deserved a high position in government. Having been refused office by Garfield and his secretary of state, Guiteau went to a hardware store in June 1880 and purchased a pistol and a box of ammunition. The voices he heard in his head told him that in killing the president, Guiteau would assure himself the ambassadorship of Great Britain, at least.

Presidents in those days lived like ordinary men. They walked downtown to Washington for haircuts and rode passenger trains to speeches. They went out in the evenings for strolls along the Mall and admitted visitors to the White House by answering the front door. And so, on the morning of July 2, 1880, when Garfield went to the Baltimore and Potomac train station, Guiteau was there waiting. Guiteau shot Garfield twice, once in the arm and once in the back. Two months later, Garfield was dead, killed as much by ineffective, even harmful doctoring as by Guiteau. He had served only 200 days and would be sorely missed by an America just then heading for further labor strife, violence, race hate, capitalist exploitation, agricultural and bank failure, and a political system run wild with partisan division.

“Destiny of the Republic” is a surprising story that includes Alexander Graham Bell, who made extraordinary attempts to invent a device to locate the bullet in Garfield’s back. It is the story of one doctor named D. Willard Bliss (his first name was actually “Doctor”) whose hubris, ignorance and pride contributed to the death of the president as much as a 50-gram piece of lead and the medicine of the time. It is a book that contains many surprising details—there were huge rats running loose in the White House and a malarial swamp just outside the back gate—that will delight and educate readers.

When Millard claims, as she does, that Garfield’s death united the country North and South, she perhaps overstates the case. The country continued to drift towards violence and division. The South soon reasserted itself as the center of segregation, lynching and white supremacy. Robber barons continued to raid the national till. Laboring people continued to suffer. If there is a fault in the book it is this lack of overall perspective, the story of a horrible time in American history. But this little-known aspect of our American story will never be told as well as Millard tells it here. The book is beautifully made, contains numerous lovely illustrations and photographs, and includes a complete bibliography.