Doctorow, E.L., Andrew’s Brain. Random House, New York, 2014 (200pp. $26)

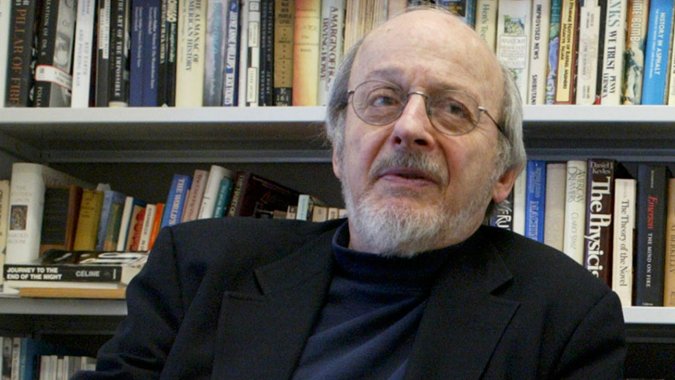

(E.L. Doctorow, one of America’s greatest writers, died recently. Here is a review of one of his last books)

The bedrock of fiction is social reality. Mostly we readers expect fictional characters to resemble real people who, though they might be boy wizards, private detectives, or time travelers, obey the reader’s emotional and cognitive expectations and therefore have something to share, teach or, most importantly, reveal. The novel of ideas, on the other hand—something like “War and Peace”, for example, exhales the didactic with particularity, each character usually “standing in” for some important movement or philosophical position. Lurking in the shadows like a literary boogieman, on the other hand, is postmodern meta-fiction (which in the 1950s and 60s was called “experimental fiction”), whose practitioners like Barthelme, DeLillo or Auster, chuck traditional narrative, sequence, social reality and verisimilitude, in favor of a text that challenges the reader to deconstruct his own experience, abandon normal expectations, and listen to other, sometimes simultaneous voices. Along the way, authorship and authority are expected to disappear.

E.L. Doctorow’s new novel, “Andrew’s Brain” is a meta-construction searching for interpretation the way a Twilight Zone driver might search for a non-existent toll booth exit from an endless, darkened (but traffic-less) freeway. The Andrew of the title is an ostensible patient to the invisible “Doc”, who listens while Andrew catalogues his woes, trials, disappointments, hopes and achievements—occasionally commenting, keeping things on track, or admonishing his “patient”, but always from a quiet corner of the page. Andrew sees himself as a major screw-up. He has good reason. His first child dies as the result of improper medication in infanthood, for which Andrew blames himself. Martha, Andrew’s first wife, leaves Andrew and Andrew meets and marries a second woman, Briony, whose parents are perfectly proportioned midgets who reside in a picturesque California town about a hundred miles south of Los Angeles. Sadly, Briony dies at the World Trade Center, though her football player high school sweetheart survives the buildings’ collapse. Bookended between these puzzling “events” is Andrew’s residence in the foothills of the Wasatch Mountains and his tenure as head of George W. Bush’s White House Office of Neurological Research where Bush himself and his morally challenged compadres Chaingang and Rumdum act like the human spam they were in real life.

Yes, Andrew is a cognitive scientist, interested in how the biological brain weighing three pounds and composed of billions of cells and synapses, running on chemical energy, readily explainable by science and easily mapped by MRI machines, becomes in God’s hands the human soul, striving for immortality or, at least, transcendence. At times during the book, Andrew is perceived, by himself, or by circumstance, to be The Pretender, The Holy Fool, or, at the White House, the Android, a nickname bestowed by the jocular Bush, with whom Andrew, by happenstance, happened to be roommates at Yale.

Getting off Doctorow’s fancifully constructed meta-freeway isn’t easy. Andrew might well be a real mental patient working through his many neuroses (The Pretender); he might well be The Holy Fool, a seeker of soul-wisdom on the outskirts of Dostoyevsky-ville; he might well be the Android, a disembodied computer generated experiment in artificial intelligence. Doctorow actually gives his reader these choices, and throws in a few choice “(thinking)” pauses in the text to encourage more meta-carnage. Unfortunately, the midgets, politicians, football player boyfriends and opera-singing husbands that populate “Andrew’s Brain” are only cartoons masquerading as ideas. Or, as Dickens would have it in “A Christmas Carol”, they are only blots of mustard or undigested bits of cheese.

At bottom, “Andrew’s Brain” is a discouraging portrait of human nature. “I thought how contention makes us human,” Doctorow writes. “How every form of it is practiced religiously, from gentlemanly debate to rape and pillage, from dirty political attacks to assassinations. Our nighttime street fights outside of bars, our slapping arguments in plush bedrooms, our murderous mutterings in divorce courts. We had parents who beat their children, schoolyard bullies, career-climbing killers in ties and suits….”, and so on for a full page, down and down through kick-boxing, Ponzi schemes and war. This is one thing we readers can certainly second.

Doctorow is a great American writer, responsible for classics like “Ragtime”, “Billy Bathgate” and “Loon Lake,” among other great works. “Andrew’s Brain” is, sadly, one of those difficult literary eruptions, a beautifully written bad book. His theme—what makes a brain into a soul, is important. In fact, Edward O. Wilson’s recently published “Letters to a Young Scientist” takes up this theme with clarity and grace, contemplating insect and plant intelligence, swarm minds, and the seeming social soul of bees and termites, as clues to what makes our human “mind” unique. And of course, philosophers have struggled for centuries with the “mind body problem”.

But a theme, even an important meta-theme, is too little to ask from a writer. What “Andrew’s Brain” lacks is, oddly, a soul.