Doctorow, E.L. All the Time in the World: New and Selected Stories, Random House, New York, 2011 (277pp.$26)

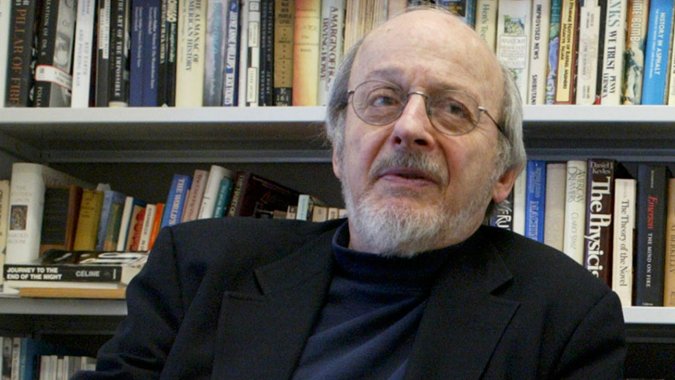

(E.L. Doctorow, one of our great American writers, died recently. In his honor, here is a review of one of his books.)

A great short story is the supernova of fiction, exploding brilliantly, pouring out its light, and then disappearing suddenly in a diaspora of revelation and concealment. Unlike the novel, which, like a marriage, demands commitment despite much boredom and occasional betrayal, and which may end in many different ways, the short story is more like a torrid adulterous affair. Both parties leave the hotel terrified.

E.L. Doctorow is the grand novelist whose fiction includes the justly famous “Ragtime,” “Loon Lake,” “World’s Fair,” and “The Waterworks.” Among his honors are the National Book Award, three National Book Critics Circle awards, two Pen/Faulkner awards and the National Humanities Medal.

The short stories collected in “All the Time in the World” come from his middle and late career, and some are no more than dressed-up outtakes from novels like “Billy Bathgate” and “City of God” (the stories being “Liner Notes: The Songs of Billy Bathgate” and “Heist” form “City of God”). Others were published in the New Yorker magazine, the Kenyon Review, and even in previous collections. And while not all of them succeed on the supernova level, at least four are brilliant, captivating and mysterious, the kind of torrid affair a writer and reader might savor.

Most of the characters in this collection are on the run. What brilliant conceit caused Doctorow to dream up the middle-class bourgeois man who leaves his wife one day only to wind up “living” in the garage attic behind the house, observing what happens in the months and years subsequent to his disappearance, scrounging the neighborhood for food? As Doctorow beings “Wakefield”: “I had no thought of deserting her. It was series of odd circumstances that put me in the garage attic with all the junk furniture, and the raccoon droppings—which is how I began to leave her, all unknowing, of course—whereas I could have walked in the door as I had every evening after work in the fourteen years and two children of our marriage.” This man, a respected fellow, grows a shaggy beard, eats out of garbage cans, spies on his wife and befriends schizophrenics in a halfway-house. How shall this end? It is a memorable story with a barb in its tail.

In “Assimilation,” another story of outsider desperation, a dish washer named Ramon agrees to marry an eastern European illegal immigrant for money, only to find himself the victim of fraud by a group of mangy thugs. In an utterly captivating story called “Edgmont Drive,” a bitterly divided couple are confronted by a homeless poet at their front door. The poet used to live in the house, but lost it by misadventure and is now sleeping in a car. He visits. He lingers. He is pitied by the wife. He moves in and finally dies in the guest room. The genius of Doctorow is to make us apprehensive, then concerned, and finally uneasy as we leave the hotel terrified.

In a curious story titled “A House on the Plains,” clearly set in the early part of the 20th century, a mother and son move from Chicago to the plains of a town simply called “La Ville” (the town) and promptly begin to set up lonely bachelors for murder and theft. Simply and plainly rendered, the story reminds one of an episode of “Alfred Hitchcock Presents’ in the calmness of its horror. In “A Writer for the Family” the son of a dead father must, for financial reasons, continue to write letters to his grandmother pretending that the dead father has simply moved to Phoenix to set up a successful business, a fascinating premise that is almost realized.

A number of stories are drab failures. “Walter John Harmon” tells the story of a religious cult in the desert and its betrayal by a founder too fond of booze and women. Sadly, it goes nowhere and falls flat. One story titled “Willi” is absurdly incomprehensible.

Doctorow is an extraordinarily accomplished stylist. In one of the “Liner Notes” pieces from “Billy Bathgate,” the main character (a songwriter) describes how he came to write a tune about W.C. Fields: “And so it is in the form of a walking song, it walks me through the underworld of the dreaming masses, where this pudgy demon of truth, Mr. W.C. Fields, with his dirty top hat, his run-down elegance of manners, his drunken scrollwork of a personality, resides like the Chief Official over the technology of our souls.”

Most of us would give our eyeteeth to write a sentence half as good as that.