Guinn, Jeff. Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson, Simon and Schuster, New York, 2013 (495pp.$27.50)

He was a disagreeable child who lied about everything and blamed others for his misdeeds. Without a father and scrawny to a pitiable degree, Little Charlie compensated by acting out, making people uneasy, and becoming the center of attention, utilizing his only gifts. Sister Kathleen and his Uncle Luther were in jail at Moundsville, West Virginia on a robbery conviction and Charlie was sent to live with his Aunt Glenna in the hardscrabble bottoms of the Ohio River coal country in McMechen, a railroad town.

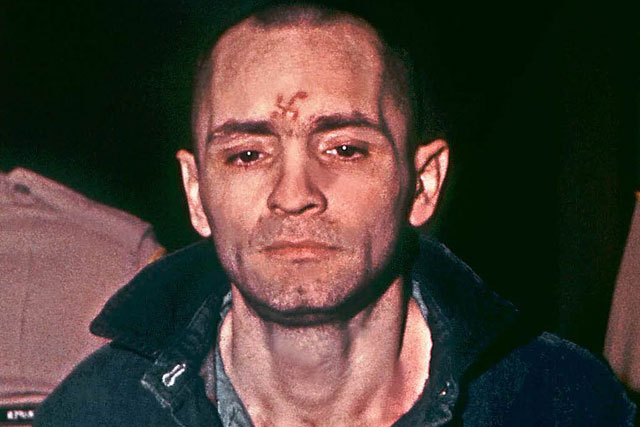

Sociopaths like Charles Manson are squalid characters whose nickel-and-dime lives rarely rise above petty criminality. Occasionally though, their manipulative wiles, unhampered by considerations of conscience or emotion, break through society’s defenses in spectacular instead of humdrum ways. Sometimes their lies move nations and they become, like Stalin, political criminals at the head of party organizations; and sometimes a flair for organization like that exhibited by Al Capone creates a hydra-headed crime syndicate. Manson’s talent was evident—at one point, he led a small cult of about dimpled smile, shy good looks, and penetrating black eyes to express something—nobody knew quite what. Grandmother Nancy, an eastern Kentucky hill-lady, thumped the Bible so regularly that before adolescence Charlie knew all about the Revelations promising Apocalypse and Hellfire. By the time the kid was five years old, his mother was worried. As an adult, Charlie had followers numbering about thirty members, most of them latently self-destructive young women, runaways, drug addicts and disturbingly damaged flower children.

Jeff Guinn’s new true crime book Manson does its level best coming to terms with the mundane reality that was Charlie and his followers. Far superior to Vincent Bugliosi’s boring and self-promoting best-seller from the 70s called “Helter Skelter”, and more detailed and better-researched than poet Ed Sander’s famous “The Family”, Guinn takes a stab at doing for Manson what Norman Mailer did for Gary Gilmore in “The Executioner’s Song”, that Pulitzer Prize-winning nightmare. Guinn’s modus involves placing Manson in the context of the times, a running film of American history from the 1930s through the heady, paranoid and violent days of the late 1960s when Manson and the family were running hot on dreams of violent revolution from which they’d hide by going down a hole in the Death Valley Desert, reemerging to control the planet.

The story is all here—Charlie in juvenile prisons from Boy’s Town to Chillocothe, Illinois to the National Center in Washington, then on to Federal prison at Terminal Island in LA and McNeil in Washington State. In prison Charlie took a four-month course in Dale Carnegie’s methods to win friends and influence people. Later, he met a con who introduced him to Scientology. Behind bars, Charlie found his métier. Reformatories and prisons spit him out onto Haight-Ashbury in 1967, along with a flood of America’s lost children who would eventually become Charlie’s fodder, four of whom would commit seven grisly murders infamous in American history.

Guinn is the author of a number of excellent “true crime” works, including books about the O.K. Corral and Bonnie and Clyde. To his credit, he unearths a number of new sources about Manson’s early life. Guinn managed to conduct interviews with Manson’s sister and cousin, some of his cellmates, and even members of the Family. Manson’s dream of rock stardom, his worship of the Beatles, his connections to Dennis Wilson of Beach Boys fame and his obsession with race-war dovetail with a more primal End Times philosophy having its roots deep in America’s religious psychology.

The book is best at following Charlie’s difficult early life where we almost—almost, feel sorry for him. That’s something sociopaths really dig. But halfway through the story, now focused on Charlie’s pitiful cultists, the Bikers and drug-dealers who hang around the story like malevolent ghosts, the brutal, senseless murders and, finally, the sensational trials dominated by self-aggrandizing, self-promoting, show-boating lawyers, time runs out on both Manson the man and Manson the narrative and the reader loses patience. As a book, it’s a well-made thing, with a section of unusual photographs, excellent notes and a fine bibliography.

But it is hard to learn something from a story like this. Maybe Joan Didion explained it best in “White Album”, that brilliant essay on the August 1969 paranoia fulfilled. And maybe, just maybe, we should run from guys who preach Utopia through Surrender.

public domain

May 20, 2015 -

Hello! This post could not be written any better! Reading through this post reminds me

of my good old room mate! He always kept talking about this.

I will forward this page to him. Pretty sure he will have a good read.

Thank you for sharing!

Gaylord Dold

May 20, 2015 -

Hello,

Thanks for your kind words. Perhaps the Joan Didion

essay on Manson is for you too. It’s insightful and

scary and on the mark. Take care.